RECAPITULATION AND SUPPLEMENT

I. WHETHER SANCTIFYING GRACE

IS A FORMAL PARTICIPATION IN DEITY AS IT IS IN ITSELF

(We here reprint an article which

appeared in the Revue Thomiste, 1936.)

“Grace, which

is an accident, is a certain participated likeness of the divinity

in man” (St. Thomas, IIIa, q. 2, a. 10 ad I).

This question

has been put to us in connection with recent debates

and with reference to what we

recently wrote in the Revue Thomiste on the subject of Deity.

More precisely, the question

was formulated as follows: Is grace a participation in Deity as it

is in itself and as seen by the blessed, or only in Deity as

imperfectly known by us? This latter aspect could be further

differentiated: Is it a question of Deity as imperfectly known by

the philosopher, or as known by the theologian-wayfarer?

State of

the question. In order to

grasp better the sense of the terms, let us recall what we have

discussed elsewhere

at greater length. The Deity

as it is in itself remains naturally unknowable, and even cannot be

known except by the immediate vision of the blessed. But among the

divine perfections which it contains formally in its eminence, which

we know by natural means, is there not one which has priority over

the others, from which the others can be deduced, as the properties

of man are deduced from his rationality?

The

controversy on this subject, relative to the formal constituent of

the divine nature according to our imperfect mode of knowledge, is

well known. Even the Thomists themselves are not in complete accord

on this point. Some maintain that this formal constituent is

subsistent being itself, according to the words of Exod. 3:14: “I am

who am,” because all the divine attributes are deducible therefrom.

Others hold that it is subsistent intellection (intelligere

subsistens). We have explained elsewhere

why we accept the first solution, on account of the text from

Exodus, of the radical distinction between subsistent being

andcreated being, and because all the divine attributes are

deducible from it. Does not St. Thomas accordingly delay treating of

the divine intelligence until question fourteen of the First Part,

after he has deduced several attributes from subsistent being

itself?

Whatever may

be the issue of this discussion, it remains true for all Thomists

that Deity as it exists in itself is superior to all the absolute

perfections which it contains in its eminence (formaliter

eminenter).

This is

evident from the fact that these perfections, which are naturally

capable of participation by creatures, such as being, life,

intelligence, are naturally knowable in a positive way, whereas

Deity is not: it is the great darkness which the mystics speak of.

It designates the very essence of God, that which is proper to Him,

His intimate life. It is the object of the beatific vision itself,

and, before that vision, it is the “obscurity from above” which

proceeds from a light too intense for the weak eyes of our souls.

From this it

can be inferred that subsistent being itself contains only in

implicit act the attributes which are progressively deducible from

it, but Deity as such contains them in explicit act, since, when it

is seen, there is no longer any need of deducing these attributes.

Deity can thus be represented as the apex of a pyramid the sides of

which would represent subsistent being, subsistent intellection,

subsistent love, mercy, justice, omnipotence, that is, all the

attributes formally contained in the eminence of Deity. To adopt a

less far-fetched symbolism, Deity in relation to the perfections

inhering in its eminence is somewhat like whiteness in relation to

the seven colors of the rainbow, with this difference: the seven

colors are only virtually present in the whiteness, whereas the

absolute perfections (being, intelligence, love, etc.) are in Deity

formally and eminently.

Thereupon the

question presents itself: Is grace a participation in the divine

nature (or in Deity), the intimate life of God as it is in itself,

or only in the divine nature as it is imperfectly conceived by us as

subsistent being or subsistent intellection?

The

theologians who have written on this subject generally concede that

grace is a participation in Deity as it is in itself, objectively

(inasmuch as it disposes us radically to see it). But some add that

it is not so intrinsically or subjectively, for Deity is infinite

and hence, as such, cannot be participated in subjectively.

Furthermore, they declare that Deity is the intimate life of God,

none other than the Trinity of the divine persons. Now grace cannot

be a subjective participation in the Fatherhood, the Sonship, the

Spiration which constitute the intimate life of God. These

theologians deduce therefrom that grace is subjectively a

participation in the divine nature as imperfectly conceived by us,

as one (not as triune) and as subsistent intellection.

It is at once evident that this viewpoint can

be interpreted in two ways, according to whether it refers to the

divine nature imperfectly known by the philosopher or to the divine

nature imperfectly known beneath the light of essentially

supernatural revelation by the theologian, who knows God, not only

under the nature of being and first being, but also under the nature

of Deity, already known obscurely by the attributes of God, author

of grace (as supernatural Providence) and, above all, by the mystery

of the Trinity. (Before the revelation of this mystery of the

Trinity, under the Old Testament, the super-natural providence of

God, author of salvation, was known.)

Basis of a solution. To the question thus

stated, we reply that, according to traditional teaching,

sanctifying grace in itself is intrinsically (and not merely in an

objective, extrinsic manner) a formal, analogical (and, of course,

inadequate) participation in the Deity as it is in itself, superior

to being, intelligence, and love, which it contains in its eminence

or formally and eminently. As Cajetan says, Ia, q. 39, a. I, no. 7:

“The Deity is prior to being and all its differences; for it is

above being and beyond unity, etc.” The reasons which we are about

to indicate are presented in progressive order, beginning with the

most general.

I. There can be no question of a participation

in the divine nature merely as conceived by the philosopher. He

does, in fact, know God as first being and first intelligence,

inasmuch as He is author of nature, but not as God, author of grace.

This is the basis of the dis-tinction between the proper object of

natural theology or theodicy (a branch of metaphysics): God under

the reason of being and as author of nature, and the proper object

of sacred theology: God under the nature of Deity (at least

obscurely known) and as author of grace. This is the classical

terminology employed by the great commentators on St. Thomas, Ia, q.

I, a. 3, 7; cf. Cajetan, Bañez, John of St. Thomas, the

Salmanticenses, Gonet, Gotti, Billuart, etc. Nowadays several

writers make use of this classical terminology from force of habit,

without apparently having pondered very deeply the difference

between the proper object of theodicy, or natural theology, and that

of theology properly so called. Nevertheless St. Thomas has

expressed this difference in very precise terms, Ia, q. I, a. 6:

“Sacred doctrine properly treats of God under the aspect of highest

cause, for it considers Him not only to the extent that He is

knowable through creatures (as the philosophers knew Him) but also

with respect to what He alone knows of Himself which is communicated

to others by revelation.” This is what later theologians referred to

as “God, not under the general reason of being, but under the

essential, intimate reason of Deity, or according to His intimate

life.” Hence in the question which engages our attention, we are not

concerned with the divine nature only as it is imperfectly conceived

by the philosopher.

2. Moreover,

only God can produce grace in an angel or in the very essence of the

soul, and He does so independently of the conception which the

philosopher or theologian holds regarding the divine nature, and

independently of any natural effect which might be the source of

these imperfect conceptions. Grace thus assimilates us immediately

to God as such in His intimate life; it is therefore a formal,

analogical participation in the Deity as it is in itself. In the

natural order, a stone has an analogical likeness to God inasmuch as

He is being, the plant inasmuch as He is living, man and angel

inasmuch as He is intelligence. Sanctifying grace, which is far

superior to the angelic nature, is an analogical likeness to God

inasmuch as He is God, or to His Deity, to His intimate life, which

is not naturally knowable in a positive way. This is why, above the

kingdoms of nature (mineral, vegetable, animal, human, angelic),

there is the kingdom of God: the intimate life of God and its formal

participation by the angels and the souls of the just.

Therefore to

know perfectly the essence or quiddity of grace, one would have to

know the light of glory of which it is the seed, just as one must

know what an oak is to know the essence of the germ contained in an

acorn. But it is impossible to know perfectly the essence of the

light of glory, essentially ordered to the vision of God, without

knowing the divine essence immediately by intuition. Hence St.

Thomas declares, in demonstrating that only God can produce grace,

Ia IIae, q. 112, a. 2: “It must be that God alone should deify,

communicating a fellowship in the divine nature by a certain

participated likeness, just as it is impossible for anything but

fire to ignite.” The word “deify” shows that grace is a

participation in the divine nature, not according to the reason of

being or intelligence merely, but by the essential, intimate reason

of Deity.

3. But in that case, it will be objected, grace

would have to be intrinsically a (subjective) participation in the

intimate life of God. Now this is none other than the Trinity of

the divine persons. There would therefore be in grace a

participation in the fatherhood, the sonship and the spiration,

which theory is a departure from traditional teaching.

The answer to this objection is

that, according to traditional teaching, and particularly that of

St. Thomas, the adoptive sonship of the children of God, ex Deo nati,

is a certain likeness to the eternal sonship of the Word. In fact we

find explicitly in IIIa, q. 3, a. 5 ad 2: “Just as by the act of

creation divine goodness is communicated to all creatures by way of

a certain similitude, so by the act of adoption a similitude of

natural sonship is communicated to men, according to the words of

Rom. 8:29: ‘Whom He foreknew . . . to be made conformable to the

image of His Son.’” And further (ibid., a. 2 ad 3):

“Adoptive

sonship is a certain likeness of eternal sonship; just as all the

things that were made in time are, as it were, likenesses of those

which were from all eternity. Man however is likened to the eternal

splendor of the Son by the brightness of grace, which is attributed

to the Holy Ghost. And hence adoption, although common to the whole

Trinity, is appropriated to the Father as its author, to the Son as

its exemplar, to the Holy Ghost as imprinting this likeness of the

exemplar upon us.”

Likewise St.

Thomas again in his commentary on Rom. 8:29 thus explains the words

“to be made conformable to the image of His Son”: “He who is adopted

as son of God is truly conformed to His Son, first, indeed, by a

right to participate in His inheritance . . . ; secondly, by sharing

His glory (Heb. 1:3). Hence by the fact that He enlightens the

saints with the light of wisdom and grace, He makes them conformable

to Himself. . . . Thus did the Son of God will to communicate to

others a conformity with His sonship, that He might not only be the

Son, Himself but also the first-born of sons. And so He who is the

only-begotten by eternal generation (John 1:18), . . . is, by the

conferring of grace, the first-born of many brethren. . . .

Therefore we are the brothers of Christ because He has communicated

a likeness of sonship to us, as is here said, and because He assumed

the likeness of our nature.”

St. Thomas

speaks similarly in his commentary on St. John’s Gospel (1:13),

explaining the words, “who are born of God.” “And this is fitting,

that all who are sons of God by being assimilated to the Son, should

be transformed through the Son. . . . Accordingly the words, ‘not of

blood, etc.,’ show how such a magnificent benefit is conferred upon

men. . . . The Evangelist uses the preposition ‘ex’ speaking

of others, that is, of the just: ‘Ex Deo nati sunt’;

but of the natural Son, he says ‘De Patre est natus.’ ” Why?

Because, as explained in the same commentary, the Latin preposition

‘de’ indicates either the material, efficient, or

consubstantial cause (The smith makes a little knife of [de]

steel); the Latin preposition ‘a’ always refers to the

efficient cause, and the preposition ‘ex’ is general,

indicating either the material or efficient cause, but never the

consubstantial cause.

Now the

objection raised was that grace cannot be intrinsically a

(subjective) participation in the Deity or the intimate life of God,

for that is none other than the Trinity of persons in which there is

no participating. The participation is in the divine nature as one.

From what has

just been explained, the reply may be made as follows: True, the

participation is in the divine nature as one, however not merely

such as conceived by the philosopher, but such as it is in itself,

in the bosom of the Trinity. It is not only a question of the unity

of God, author of nature, but of that absolutely eminent, naturally

unknowable unity which is capable of subsisting in spite of the

Trinity of persons. We are concerned with the unity and identity of

the nature communicated by the Father to the Son and by Them to the

Holy Ghost. Therein lies the meaning of the traditional proposition

which we have just read in St. Thomas: “Adoptive sonship is a

certain likeness of eternal sonship.” So has it always been

understood.

From

all eternity God the Father has a Son to whom He communicates His

whole nature, without dividing or multiplying it; He necessarily

engenders a Son equal to Himself, and gives to Him to be God of God,

Light of Light, true God of true God. And from sheer bounty,

gratuitously, He has willed to have in time other sons, adopted

sons, by a filiation which is not only moral (by external

declaration) but real and intimate (by the production of sanctifying

grace, the effect of God’s active love for us). He has loved us with

a love that is not only creative and preserving, but vivifying,

which causes us to participate in the very principle of His intimate

life, in the principle of the immediate vision which He has of

Himself and which He communicates to His Son and to the Holy Ghost.

It is thus that He has predestinated us to be conformable to the

image of His only Son, that this Son might be the first-born of many

brethren (Rom. 8:29). The just are accordingly of the family of God

and enter into the cycle of the Holy Trinity. Infused charity gives

us a likeness to the Holy Ghost (personal love) ; the beatific

vision will render us like the Word, who will make us like unto the

Father whose image He is. Then the Trinity which already dwells in

us as in a darkened sanctuary, will abide in us as in an

illuminated, living sanctuary, where It will be seen unveiled and

loved with an inamissible love.

The only Son

of God receives the divine nature eternally, not merely as it is

conceived by the philosopher (as being itself or even as subsistent

intellection), but as it is in itself (under the reason of the Deity

clearly perceived). Consequently He received the unity of that

nature, not only as conceived by the philosopher, but as it is

capable of subsisting in spite of the Trinity of persons really

distinct one from another. He receives with Deity the essential

intellection common to the three persons, which has for its primary

object the Deity itself known comprehensively. He also receives

essential love, not only as known by the philosopher, but that

essential love which, remaining numerically the same, belongs to the

three persons, since they love one another by one sole, identical

act, just as they know one another by the same, identical

intellection.

Now according

to traditional teaching, as we have just seen, sanctifying grace

makes us children of God by an analogical, participated likeness to

the eternal sonship of the Word. Hence, in us, it is a participation

in Deity as it is in itself, not only under the nature of being or

under the nature of intellection, but under the nature of Deity, and

not only a participation in Deity as known obscurely by the

theologian through created concepts, but as it is in itself and seen

as it is by the blessed.

Such is the

true sense of these assertions, admitted by all theologians. But

their profundity does not always receive sufficient attention. The

mineral already resembles God analogically as being, the plant and

animal as living, man and angel as intelligent; but the just man by

grace resembles God precisely inasmuch as He is God, according to

His very Deity or His intimate life as it is in itself. Thus the

just man penetrates, beyond the human kingdom of reason, beyond the

angelic kingdom, into the kingdom of God; his life is not merely

intellectual but deiform, divine, theological: “it is deified,”

according to St. Thomas, Ia IIae, q. 112, a. I.

That is truly

the formal aspect of the life of grace, what is proper to it,

unique, significant, and interesting. Thereby it is a formal,

although inadequate and analogical, participation in the divine

nature as it is in itself, or of Deity as such. This is found above

all in con-summate, inamissible grace received into the essence of

the soul, and also in the light of glory received into the intellect

by the beatified soul, and in the charity received into its will.

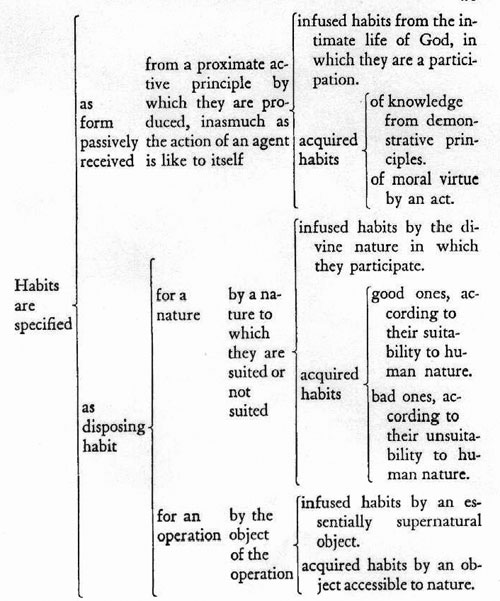

4. It is, then, materially (in the

theological sense of the term) that grace is a finite accident (an

entitative habit received into the essence of the soul), that

infused faith is an operative habit received into our intellect, and

charity an operative habit received into our will. All of this is

true by reaTon of the receptive subject. But these habits are a

formal participation in the intimate life of God; otherwise they

would not dispose us to see it as it is in itself by an immediate

vision that will have the same formal object (objectum formale

quod et quo) as the uncreated vision which God, one in three

persons, has of Himself.

This

distinction of what grace is either materially or formally, is

similar to the one that is generally made in the natural order

between intelligence and the created mode whereby it exists in us

and in the angels, as a

faculty (accident) distinct from the substance of the soul or of the

angel, distinct also from the act of intellection. This is quite

true and does not prevent intelligence as such from being an

analogical perfection, the formal notion of which does not imply any

imperfection, and which, consequently, is to be found properly and

formally in God as subsistent intellection. In the same way, the

perfection of wisdom is distinguished from its created mode whereby,

in us, wisdom is measured by things, whereas in God it is the

measure and cause of things.

From the same

more or less material standpoint, when sanctifying grace is compared

to faith and charity, it may be said that grace is a participation

in the Deity as a nature, faith a participation in the Deity or

intimate life of God as knowledge, and charity a participation in

that intimate life as love. But it is always a question of formal

participa-tion in the intimate life of God or in the Deity in its

eminent unity, not such as it is known by the philosopher, but as it

is in itself in the Trinity.

Moreover, sanctifying grace cannot be an

objective participation in the Deity as it is in itself (and dispose

us radically to immediate vision) without being intrinsically

specified by it, that it, without having an essential (or

transcendant) relationship to the Deity as it is in itself.

Hence, in his reply to Father Menéndez Rigada, Father Gardeil

recognizes, with reference to the passage from the Salmanticenses

which we have just indicated in a note, that “it does not seem

possible for the intuition of the divine persons to originate in

sanctifying grace, if the latter is not a kind of exemplary

participation in the divine nature inasmuch as it subsists in the

divine persons. For, as the Salmanticenses declare (loc.

cit.), the inclination toward an object should originate in some

participation in the object aimed at.” Yes, for there is here, not

an accidental, but an essential (or transcendant) relationship

between grace and Deity seen immediately. This argument clarifies

the last problem which we are about to propose.

6. In the light of what immediately precedes,

it is apparent that subsistent intellection (intelligere

subsistens), even considered subjectively, is no less infinite

than subsistent being, or than Deity as it is in itself. Granted

that sanctifying grace can be a participation in the divine nature

as intellection, one should admit that it can be a participation in

Deity as it is in itself.

If it is objected: but Deity as it is in itself

is, like subsistent being, infinite and therefore cannot be

participated in subjectively or intrinsically, the reply in the

words of Father Gardeil is as follows:

“That would be true if a participation could be adequate, but

it could be only imitative and analogical.” The Salmanticenses (o.p.

cit., no. 64) are in accord: “Therefore in the mind of St.

Thomas it is perfectly consistent for grace to participate, that is,

to imitate, the whole being as to its essence and infinity, although

it does not correspond to it adequately in all its predicables but

only partially.

Deity is thus

identified with subsistent being itself (inasmuch as it contains

being and the other absolute perfections formally and eminently),

whereas in us the formal, analogical participation in Deity takes

the form of an accident. This is the more or less material, not

formal, aspect of sanctifying grace, just as in the natural order

there is a difference between the perfection of intelligence and the

created mode whereby it is in us a faculty distinct from the

substance of the soul and the act of intellection.

Conclusion.

For these various reasons, of which the first are more general and

are presupposed according to our mode of cognition, we consider

sanctifying grace to be a formal, analogical participation in Deity

as it is in itself. Two important corollaries follow from this:

1. It can be seen manifestly, as we have

established elsewhere,

that reason alone is incapable (for instance, by the natural,

conditional, inefficacious desire to see God) of demonstrating

precisely the possibility of grace, the possibility of a formal,

analogical participation in the Deity or intimate life of God which

would be, materially, a finite accident of our souls. Of this

possibility reason can give a proof of suitability, but not an

apodictic proof, for, of itself, reason cannot know the Deity or

intimate life of God positively. “This possibility of grace,” as is

commonly taught, “is neither proved nor disproved apodictically, but

it is urged by reason, defended against those who deny it, and held

with a firm faith.”

2. With regard

to the problem of the formal constituent of the divine nature,

according to our imperfect mode of understanding, the solution which

identifies it with subsistent intellection rather than with being

itself is not confirmed by the sequence: grace would be a

participated likeness, not of subsistent being but of subsistent

intellection. This question of the philosophically formal

constituent is of no importance here for the definition of grace,

which is in reality a participated likeness in Deity, superior to

both being and intellection which are contained in its eminence,

that is, formally and eminently.

The doctrine

we have just presented is found in St. Thomas, Ia, q. 13, a. 9:

“This name of God is not communicable to any man according to the

fullness of its meaning, but something of it is so by a kind of

likeness, so that they may be called ‘gods’ who participate by such

a likeness in something of the divinity, according to the words

of psalm 81:

‘I have said: You are gods.’ ” And the answer to the first

objection: “The divine nature is not communicable except by the

participation of likeness.” Likewise IIIa, q.2, a.6 ad I. Cf.

Salmanticenses, De gratia, disp. IV, the quiddity and

perfection of habitual grace, dub. IV, nos. 62, 63, 7072, where the

participation by formal, analogical imitation is very well defined;

also John of St. Thomas and Gonet, quoted in the same place.

NOTE

SUPERNATURAL AND NATURAL

BEATITUDE

In his volume entitled

Surnaturel (Etudes historiques, 1946), p. 254, Father H.

de Lubac, having examined certain texts of St. Thomas on the

distinction between the natural and the supernatural, writes as

follows: “At any rate, nothing in his works declares the distinction

which a certain number of Thomistic theologians would later concoct

between ‘God the author of the natural order’ and ‘God the object of

supernatural beatitude.’ . . . Nowhere, explicitly or implicitly,

does St. Thomas refer to a ‘natural beatitude.’” It is evident that

Father de Lubac has never explained the Summa theologica

article by article.

St. Thomas

says, Ia, q. 23, a. I, Whether men are predestined by God: “It

pertains to providence to ordain a thing to its end. But the end

toward which created things are ordained by God is twofold. One,

which exceeds the proportion and faculty of created nature, is

eternal life, which consists of the divine vision and which is

beyond the nature of any creature as is shown above (Ia, q. 12, a.

4). The other end, however, is proportioned to created nature, such,

that is, as a creature can attain to by the power of its nature.

Again in the

De veritate, q. 14, a. 2: “The final good of man, which first

moves the will as to its final end, is twofold. One good is

proportioned to human nature, since natural powers are sufficient to

attain it; this is the happiness of which the philosophers have

spoken. It is either contemplative, consisting in the act of wisdom,

or active, consisting first in the act of prudence and accordingly

in the acts of the other moral virtues. The other good of man

exceeds the proportion of human nature, since natural powers do not

suffice to attain it, nor even to conceive or desire it; but it is

promised to man by the divine bounty alone.” The whole article

should be read; it affirms that “in human nature itself there is a

certain beginning of this good which is proportioned to nature,” and

further that infused “faith is a certain beginning of eternal life.”

St. Thomas

also declares, Ia IIae, q. 62, a. I: “The beatitude or happiness of

man is twofold. One sort is proportioned to human nature, that which

man can attain by the principle of his nature. But the other is a

beatitude surpassing human nature, to which man can attain only by

divine power, by means of a certain participation in divinity,

according to the words of St. Peter’s Second Epistle (1:4): ‘By

these [the promises of Christ] . . . you may be made partakers of

the divine nature.’ ” St. Thomas speaks similarly with reference to

angels, Ia, q. 62, a. 2.

He even

affirms, II Sent., dist. 31, q. I, a. I ad 3: “In the

beginning when God created man, He could also have formed another

man of the slime of the earth and have left him in his natural

condition; that is, he would have been mortal, passible, and have

experienced the struggle of concupiscence against reason; this would

not have been derogatory to human nature, since it follows from the

principles of nature. Nor would any reason of guilt or punishment be

attached to this defect, since it would not be caused voluntarily.”

This is indeed evident for, if sanctifying grace and likewise the

gift of integrity and immortality are gratuitous or not due (as

defined against Baius), it follows that the merely natural state

(that is, without these gratuitous gifts) is possible both from the

part of man and from that of God.

Is

sanctifying grace a permanent gift in the just, like the infused

virtues? Of recent years an opinion has been expressed according to

which sanctifying grace is not a form or a permanent, radical

principle of supernatural operations, but rather a motion.

It is nevertheless certain

that the infused virtues, especially the three theological virtues,

are, within us, permanent principles of supernatural operations and

meritorious as well; and it is no less certain that sanctifying or

habitual grace is the permanent root of these infused virtues. It is

not therefore merely a transitory motion, nor even a motion

unceasingly renewed in the just man as long as he preserves

friendship with God. The Fathers always referred to the theological

virtues and to sanctifying grace which they presuppose as their

radical principle.

The Council

of Trent leaves no room for doubt on this point. Denzinger in his

Enchiridion sums up the definitions and declarations of the

Church very correctly in the formula: “Habitual or sanctifying grace

is distinct from actual grace (nos. 1064 ff .); it is an infused,

inherent quality of the soul, by which man is formally justified

(nos. 483, 792, 795, 799 ff., 809, 821, 898, 1042, 1063 ff.), is

regenerated (nos. 102, 186), abides in Christ (nos. 197, 698), puts

on a new man (no. 792), and becomes an heir to eternal life (nos.

792,799 ff .).

II. THE PRINCIPLE

OF PREDILECTION AND EFFICACIOUS GRACE“

Since the

love of God is the cause of the goodness of things, nothing would be

better than another were it not better loved by God” (St. Thomas,

Ia, q. 20, a. 3).

One

of the greatest joys experienced by the theologian who, for long

years, has read and explained each day the Summa theologica

of St. Thomas, is to glimpse the sublime value of one of those

principles, often invoked but not sufficiently contemplated, which

by their simplicity and elevation form, as it were, the great

leitmotivs of theological thought, containing in themselves

virtually entire treatises. The great St. Thomas formulated them

especially toward the end of his comparatively short life, when his

contemplation had reached that height and simplicity which one

associates with the intellectual vision of the higher angels, who

encompass within a very few ideas vast regions of the intelligible

world, metaphysical landscapes, so to speak, composed not of colors

but of principles, and illumined from above by the very light of

God.

Among these

very lofty, very simple principles upon which the contemplation of

the Angelic Doctor paused with delight, there is one to which

sufficient attention is not generally paid and yet which contains in

its virtuality several of the most important treatises. It is the

principle which we find thus formulated, Ia, q. 20, a. 3: “Since the

love of God is the cause of the goodness of things, none would be

better thari another, were it not better loved by God.” In article 4

of the same question, the same principle is thus stated: “If some

beings are better than others it is because they are better loved by

God.” In short: no creature is better than another unless it is

better loved by God. This may be called the principle of

predilection, for principles derive their names from their

predicates.

This is the

principle against which all human pride ought to dash itself. Let us

examine: 1. its bases, necessity, universality, 2. its principal

consequences according to St. Thomas himself, and 3. by what other

principle it should be balanced so as to maintain in all their

purity and elevation the great mysteries of faith, particularly

those of predestination and the will for universal salvation.

THE BASIS,

NECESSITY, AND UNIVERSALITY OF

THE PRINCIPLE OF PREDILECTION

This principle,

“no creature is better than another unless better loved by God,”

seems at the outset to be manifestly necessary in the philosophical

order. If the love of God is, in fact, the cause of the goodness of

creatures, as St. Thomas affirms in the first text quoted, no one

can be better than another except for the reason that it has

received more from God; this greater goodness in it, rather than in

another, obviously comes from God.

As will be

seen, this principle of predilection is a corollary of the principle

of effcient causality: “Every contingent being or good requires an

efficient cause and, in the final analysis, depends upon God the

first cause.” It is also a corollary of the principle of finality:

“Every agent acts for an end”; consequently the order of agents

corresponds to the order of ends,

the first agent produces every good in view of the supreme end,

which is the manifestation of His goodness, and hence it is not

independently of Him or of His love, that one being is better than

another, the plant superior to the mineral, the animal to the plant,

man to the animal, one man to another, either in the natural order

or in the order of grace.

It is also

apparent from reason alone that this principle is absolutely

universal, valid for every created being from a stone to the

hightest angel, and not merely applicable to their substance, but to

their accidents, qualities, actions, passions, relations, etc., for

whatever is good in them and better in one than another, whether it

is a question of physical, intellectual, moral, or strictly

spiritual values.

The principle of predilection is also

supported by revelation under various aspects in both the Old and

New Testaments; it is even applied therein to our free, salutary

acts. Our Lord tells us: “Without Me you can do nothing”

in the order of salvation. St. Paul explains this by saying: “It is

God who worketh in you, both to will and to accomplish, according to

His good will”;

“Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not

received? And if thou hast received, why dost thou glory, as if thou

hadst not received it?”

The principle in question is contained in many other texts cited by

the Council of Orange:

“Unto you it is given for Christ, not only to believe in Him, but

also to suffer for Him”;

“Being confident of this very thing, that He, who hath begun a good

work in you, will perfect it unto the day of Christ Jesus”;

“By grace you are saved through faith, and that not of yourselves,

for it is the gift of God”;

Now concerning virgins . . . I give counsel, as having obtained

mercy of the Lord, to be faithful.”

Again we find: “Do not

therefore, my dearest brethren. Every best gift, and every perfect

gift, is from above, coming down from the Father of lights, with

whom there is no change, nor shadow of alteration”;

“No man can say the Lord

Jesus, but by the Holy Ghost”;

“Not that we are sufficient to think anything of ourselves, as of

ourselves: but our sufficiency is from God.”

That is

clearly the principle of predilection or of the source of what is

better. St. Augustine often expresses it in commenting on the

scriptural texts which we have just quoted together with several

others from the Epistle to the Romans (chapters 8, 9, and 11). He

applies it not only to men but to angels, regarding whom there is no

question of the fact of original sin (by title of infirmity,

titulus infirmitatis) but only of right, of the dependence (titulus

dependentiae) of the creature upon the Creator, both in the

natural order and in the order of grace. He observes that those

angels who attained supreme beatitude received greater aid than the

others, “amplius adjuti.”

St. Thomans

discerned an equivalent formula of the principle of the origin of

superiority in the Council of Orange and the scriptural texts cited

by it. He writes, in fact, with reference to predestination, in

rendering an account of the condemnation of the Semi-Pelagians who

attributed the beginning of salvation to man and not to God: “But

opposed to this is what the Apostle says (II Cor. 3:5), that we are

not sufficient to think anything of ourselves, as of ourselves.

However no principle can be found anterior to thought. Hence it

cannot be said that any beginning exists in us which is the cause of

the effect of predestination.” The reader is no doubt acquainted

with the texts of the Council of Orange (can. 4; cf. Denz., nos.

177-85): “If anyone holds that God waits upon our will to cleanse us

from sin, and does not admit that even our willing to be cleansed is

brought about by the infusion and operation of the Holy Ghost, he

resists the Holy Ghost Himself . . . and the salutary preaching of

the Apostle: ‘It is God who worketh in you, both to will and to

accomplish, according to His good will’ (Phil. 2:13).” Canon 9 on

the help of God asserts: “It pertains to the category of the divine

when we both think rightly and restrain our steps from falsehood and

injustice; for whatever good

we may do, God operates in us

and with us to enable us to operate”; and canon 12 on the quality in

which God loves us: “God so loves us according to the quality we

shall have by His gift, and not as we are by our own merit.” This

text taken from the fifty-sixth Sentence of St. Prosper summarizes

the one preserved in the Indiculus de gratia Dei, a

collection of anterior statements by the Holy See wherein we read (Denz.,

nos. 133-4): “No one uses his free will well except through Christ”;

“All the desires and all the works and merits of the saints should

be referred to the glory and praise of God, for no one pleases Him

otherwise than by what He Himself has bestowed.” This is essentially

the principle of the origin of superiority in a formula almost

identical with the one which St. Thomas was to give later (Ia, q.

20, a. 4). The same Indiculus preserves the following (Denz.,

nos. 135, 137, 139, 141, 142): “God so works in the hearts of men

and in the free will itself, that a devout thought, holy counsel and

every movement of good will is from God, since we can do some good

through Him without whom we can do nothing (John 15:5)”; and

likewise, no. 139: “The most devout Fathers taught the beginnings of

good will, the growth of commendable desires, and perseverance in

them to the end is to be referred to the grace of Christ . . .”;

“Hearkening

to the prayers of His Church, God deigns to draw many souls from

every kind of error, and once they are rescued from the power of

darkness He transports them into the kingdom of the Son of His love

(Col. 1:13), that from vessels of wrath He might fashion vessels of

mercy (Rom. 9:22). All this is regarded as of divine operation to

such an extent that gratitude may always be referred to God as

effecting it.”

The end of

this famous Indiculus is well-known: “Let us acknowledge God to be

the author of all good dispositions and works . . . Indeed, free

will is not taken away but rather liberated by this help and gift of

God . . . He acts in us, to be sure, in such wise that nothing

interior is to be withdrawn from His work and regard; this we

believe to satisfy adequately, whatever the writings taught us

according to the aforesaid rules of the Apostolic See” (Denz., no.

142). Is this not equivalent to saying: “In the affair of salvation

everything comes from God”? “Nothing interior is to be withdrawn,”

as the last text quoted declares. If, then, one man is better than

another, especially in the order of salvation, it is because he has

been loved more by God and has received more. This is the meaning

of: “What hast thou that thou hast not received?” quoted by the

Council of Orange (Denz., nos. 179, 199). The sense in which the

same Council speaks of God the author of every good, whether natural

or supernatural, is explained by the definition contained in canon

20: “Nothing of good can exist in man without God. God does many

good things in man which are not done by man; but man does nothing

good which God does not grant it to him to do” (Denz., no. 193); and

canon 22: “No one has anything of his own but lying and sin. But if

a man possesses anything of truth and justice it comes from that

fountain for which we should thirst in this desert, so that,

refreshed, as it were, by a few drops from it, we may not faint on

the way.” Cf. in the Histoire des Conciles of C. J. Héflè,

translated, corrected, and augmented with critical notes by Dom. H.

Lecleroq, Vol. II, Part II, pp. 1085-1110, the passages from St.

Augustine and St. Prosper from which these canons of the Council of

Orange are drawn, as confirmed by Boniface II; the most interesting,

of course, are those concerning the beginning of salvation and final

perseverance (“persevering in good works”) for both of which they

affirm the necessity of a special, gratuitous grace (Denz., nos.

177f., 183). But the grace of final perseverance is that The Semi-Pelagians,

reducing predestination to a foreknowledge of merits, held that from

the height of His eternity God desires equally the salvation of all

men and that He is therefore rather the spectator than the author of

the fact that one man is saved rather than another. Is this true or

not? Such was the profound question which confronted thinkers at the

time of the Semi-Pelagian heresy, as anyone will recognize who reads

St. Augustine and St. Prosper.

But did the Council of Orange leave it

unanswered? It asserted the principle of predilection, affirming, as

everyone admits, the necessity and gratuity of grace which is not

granted to all in the same manner, and demonstrating that in the

work of salvation everything, from beginning to end, is from God,

who anticipates our free will, supports it, causes it to act without

doing it any violence, lifts it up often, but not always; and

therein lies the very mystery of predestination. So true is this

that, heneceforth, to avoid Semi-Pelagianism it will always be

necessary to admit a certain gratuity in predestination.

Is not the

incontrovertible principle of all this teaching that all good

without exception comes from God, and that if there is more good in

one man than in another, it cannot be so independently of God? ‘“For

who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not

received ?” This text, according to St. Augustine, should cause us

to admit that there is no sin committed by any other man that I am

not capable of committing under the same circumstances, as a result

of the weakness of my free will or of my own frailty (the apostle

Peter denied his Master thrice); and if, in fact, I have not fallen,

if I have persevered, it is no doubt because I have labored and

struggled; but without divine grace I should have accomplished

nothing. Such was the thought of St. Francis of Assisi at the sight

of a criminal condemned to death. St. Cyprian had said (Ad Querin.,

Bk. III, chap. 4, PL, IV, 734): “We should glory in nothing, when

nothing is our own.” St. Basil asserts (Hom. 22 De humitate):

“Nothing is left to thee, O man, in which thou canst glory . . . for

we live entirely by the grace and gift of God.” And St.’ John

Chrysostom adds (Serm. 2, in Ep. ad Coloss., PG, LXII, 312): “In

the affair of salvation everything is a gift of God.”

THE PRINCIPAL APPLICATIONS OF

THE PRINCIPLE OF

PREDILECTION, ACCORDING TO

ST. THOMAS

St. Thomas deduces therefrom, in the

first place, the reason for the inequality of creatures, Ia, q. 47,

a. I: “The distinction and multitude of things is from the design of

the first agent who is God; for He brought creatures into existence

in order to communicate His goodness to them and be represented by

them. And since He cannot be adequately represented by one creature,

He produced a multitude of diverse creatures”; and article 2: “And

unequal . . . because a formal distinction [which is paramount]

always requires inequality.” By creation God willed to manifest His

goodness, but it could not be sufficiently represented by one

creature, which would be too deficient and limited for that. Hence

He desired many and these unequal and subordinate one to another,

for the mere material multiplication of individuals of the same

species is much less representative of the richness of divine

goodness than a multiplicity of species, hierarchically arranged as

are numbers. Leibnitz remarked that there would be no satisfaction

in having a thousand copies of the same edition of Virgil in one’s

library. But among these unequal creatures, one is better than

another only because it has received more from God.

St. Thomas

draws from the same principle the reason why grace is not equal in

all men, Ia IIae, q. 112, a. 4: “It cannot be said,” he remarks,

“that the primary reason for this inequality arises from the fact

that one man has prepared himself better than another to receive

grace, for this preparation does not pertain to man except so far as

his free will is moved by God. Hence the primary reason for this

difference must be found in God who dispenses the gifts of His grace

in diverse ways, so that the beauty and perfection of the Church may

come forth from these different degrees.” God sows a more or less

choice divine seed in souls according to His good pleasure with the

beauty of His Church in view.

St. Thomas

also deduces from this principle of the origin of superiority that

if one man prepares himself better than another for justification it

is because, in the last analysis, he received more help from a

stronger actual grace. In fact the holy doctor states in his

commentary on St. Matthew (25:15) with reference to the parable of

the talents: “He who strives harder receives more grace, but the

fact that he does strive requires a higher cause.” Again on the

Epistle to the Ephesians (4:7), with respect to the words, “To every

one of us is given grace, according to the measure of the giving of

Christ,” St. Thomas comments: “This difference is not owing to fate

or chance or merit, but to the giving of Christ, that is, to the

extent to which Christ measured it out to us. . . . For, as it is in

the power of Christ to give or not to give, so also is it to give

more or less.”

The principle

of the origin of superiority is so evident that all theologians

would accept it, did it not imply as a consequence that grace, which

is followed by its effect, is infallibly efficacious of itself and

not on account of our consent. Yet this consequence is manifest, as

many texts of St. Thomas show. If, in fact, actual grace followed by

consent to the good were not infallibly efficacious of itself but

only through the consent which follows it, there would be the

possibility that of two men equally aided by grace one would become

better than the other by his consent; he would become better without

having been loved and aided more by God.

This reason is put forth by all Thomists.

It rests on the principle of which we are speaking and is a6rmed

equivalently in several texts of St. Thomas. It is found clearly

stated particularly in the distinction which he establishes between

consequent divine will (which bears upon every good, easy or

difficult, which will come to pass here and now) and antecedent

divine will (bearing on the good separated from the particular

circumstances without which nothing comes to pass); cf. Ia, q. 19,

a. 6 ad I : “What we will antecedently we do not will absolutely but

under a particular aspect; for the will is applied to things as they

are in themselves, and in themselves they are individual. Hence we

will a thing absolutely to the extent that we will it taking into

account all the particular circumstances, which means willing it

consequently. . . . And thus it is evident that whatever God wills

absolutely comes to pass, although what He wills antecedently may

not.” If it happens, then, that Peter becomes here and now better

than another man, whether by a facile or a difficult act, this is

because from all eternity God has so willed by consequent will.

St. Thomas adds that this consequent will is

expressed in time by a grace which is efficacious of itself; cf. Ia

IIae, q. 112, a. 3: “The intention of God cannot fail, according to

the affirmation of Augustine in the book De dono perseverantiae,

chap. 14, that those who are liberated are most certainly liberated

by the beneficence of God. Hence if it is in the designs of God who

moves, that the man whose heart He moves should obtain grace, he

will infallibly obtain it, according to the words of John 6:45:

‘Everyone that hath heard of the Father, and hath learned, cometh to

Me.’”

This proposition of St. Thomas is manifestly

very different from an apparently similar one of Quesnell,

for the latter denies freedom from necessity and admits only freedom

from coercion; moreover, he denies sufficient grace and considers

every actual grace intrinsically efficacious.

Many other

texts of St. Thomas on the intrinsic efficacy of grace might be

cited. They are well known, quoted and explained in all the

treatises on grace written by Thomists.

This conception of the

intrinsic efficacy of grace is in no way contradictory of the

traditional definition of free will, which recent historical works

have set in increasingly clear relief: “the faculty of choosing the

means in view of an end to be attained,”

so that to deviate from the true end is an abuse of liberty.

Intrinsically efficacious grace is opposed

only to a new definition of free will

which disregards the specifying object of the free act (an object

not good in every respect), a definition which will not withstand

metaphysical analysis and which is unmindful of the truth that free

will is applied not univocally but analogically to God and to man,

according to a reason not absolutely but proportionately the same,

so that the free will of man, not only as an entity but also

as such under the idea of free entity (sub ratione liberi

arbitrii) depends on God, who is not merely first being, but

first intelligence and first liberty. Freedom is a perfection in

God, and we can participate in it only analogically.

As a matter

of fact, the human will can resist efficacious grace if it so wills,

as the Council of Trent declares, but as long as the will is under

efficacious grace, it never wills to resist. Under efficacious

actual grace it never sins, for the grace which is termed

efficacious is that which is followed by its effect: consent to

good. As St. Thomas ex-plains, in the same way, a man who is seated

can stand up, he has the real, proximate power to do so; but as long

as he remains seated he never does stand up, since by virtue of the

principle of contradiction, he cannot be both seated and standing.

The new

definition of liberty: “a faculty which, assuming all the

prerequisites for acting, can either act or not act,”-if understood

in the sense: under efficacious divine motion and after the final

salutary, practical judgment, the free will not only can resist but

at times actually does-such a definition is contrary to the

principle of predilection which is a corollary of the principles of

causality and finality.

By what other principle should that of

predilection be balanced? By the following: God never commands the

impossible. St. Thomas, great contemplative even more than able

dialectician, recognizes that the Christian doctrine of

predestination and grace rises like a summit above the two opposing

chasms of Pelagianism and predestinationism. He understands that, on

undertaking the ascent of that peak, one must deviate neither to

right nor to left, neither toward a rigid doctrine which restricts

the will for universal salvation and limits sufficient grace nor

toward a contrary doctrine which denies the intrinsic efficacy of

grace. He perceives, too, that one must not come to a halt halfway

up the slope at one of those eclectic combinations which would admit

grace to be intrinsically efficacious for difficult acts conducive

to salvation and not intrinsically efficacious for facile acts

conducive to salvation. Such a solution may appear simple in

practice, but speculatively it disregards the necessity and

universality of principles with relation to divine causality,

principles which there upon lose all their value; and it adds to the

obscurity of the doctrine admitted for difficult acts the insoluble

difficulties of that which is admitted for facile acts. St. Thomas

sees in such eclectic combinations nothing but a quite human

clarity, merely apparent and without basis, substituted for the

higher obscurity of the mystery, the loftiness of which is thus

minimized. Assuredly he does not look upon this as an insoluble

question which it is useless to fathom, but rather as an object of

loving contemplation, “the terrible but sweet mystery of the love of

predilection in God: ‘Who is like to Thee, among the strong, O Lord?

who is like to Thee, glorious in holiness, terrible and

praiseworthy, doing wonders?’ (Exod. 15:11) .”

Incapable of

stopping halfway as does eclecticism, St. Thomas aspires to climb

straight toward the summit. But at a certain height the trail ends,

the path has not yet been blazed, as St. John of the Cross indicates

on the illustration representing the Ascent of Carmel. St. Thomas

perceives clearly that here on earth no one can attain to that

culminating point where it will be granted him to see the intimate

reconciliation of the will for universal salvation with gratuitous

predestination. Thus he preserves all the loftiness of the mystery

and does not seek to substitute for its sublime obscurity any vain

human clarity. But without seeing the summit (faith regards what is

not seen), he succeeds in determining where it is to be found by

means of higher principles which mutually balance one another. He

formulates these very lofty, very simple principles with such great

lucidity that they only bring out in clearer relief the superior

obscurity of the inaccessible mystery located in its true site,

there where it must be contemplated in the cloud of faith, and not

elsewhere. It is one of those most beautiful chiaroscuros which have

ever attracted and riveted the contemplation of great theologians.

The masters of former times delighted in such vistas, painted not

with pigments but with principles, wherein the luminous circle

surrounding the mystery expresses so powerfully the grandeur of

faith; vistas so manifestly surpassing those of the greatest

painters or the most beautiful musical conceptions of Beethoven or

Bach. And just as these great artists understood that har-mony is

destroyed by a discordant commingling of sharps and flats, so did

those great masters of theology strive no less to avoid the jarring

dissonance produced in such difficult questions by a sharp which

would tend toward predestinationism or a flat which would incline

toward the opposite error.

The

principles which produce equilibrium here are, on the one hand, that

of predilection: “no creature is better than another unless it is

better loved by God,” a simple interpretation of the words of

Christ: “Without Me, you can do nothing,” and of those of St. Paul:

“It is God who worketh in you, both to will and accomplish,

according to His good will”; “Who distinguisheth thee? Or what hast

thou that thou hast not received?” This principle is immutable, and

together with it that other: “All that God wills by consequent will

comes to pass, without liberty being thereby destroyed.”

On the opposite slope of the invisible,

inaccessible peak, so as to determine the point where it rises and

where the blessed contemplate it in heaven, must be recalled the

principle of St. Augustine quoted by the Council of Trent (Denz.,

no. 804): “God does not command the impossible, but by commanding He

teaches thee both to do what thou canst and to ask what thou canst

not.” This formula is sacrosanct.

Invoking several passages of St. Paul, St.

Augustine,

St. Prosper,

and St. John Damascene, the Angelic Doctor gives us the

principle of the will for universal salvation (“God . . . will have

all men to be saved,” I Tim. 2:4) in an admirable and very profound

formula which echoes the most beautiful psalms in praise of the

mercy of God. He writes (Ia, q. 21, a. 4): “Every work of divine

justice presupposes a work of mercy or of sheer bounty, and finds

therein its basis. If, in fact, God owes something to His creature,

it is by virtue of a preceding gift. If He owes a reward to our

merits, it is because He has first given us the grace to merit; if

He owes it to Himself to give us the grace necessary for salvation,

it is because, from pure liberality in the first place, He has

created us and called us to the supernatural life. . . . Divine

mercy is thus the root, as it were, or the principle of all the

divine works; it penetrates them with its virtue and governs them.

In the capacity of primary source of all gifts, it is mercy which

has the strongest influence, and it is for this reason that it

surpasses justice, which takes second place. This is why, even with

regard to things due to the creature, God in His superabundant

liberality gives more than justice requires, “et propter hoc

etiam ea, quae alicui creaturae debentur, Deus ex abundantia

suae bonitatis largius dispensat quam exigat propitio rei.” (See

also Ia, q. 21, a. 2 ad 3.) St. Thomas also affirms in the very

question dealing with predestination: “God does not deprive anyone

of what is his due.”

“He gives help sufficient to avoid sin”;

“Those to whom efficacious help is not given are denied it in

justice, as punishment for a previous sin, . . . those to whom it is

granted receive it in mercy.”

This is the echo of the psalms relating to divine mercy,

particularly Ps. 135: “Praise the Lord, for He is good: for His

mercy endureth forever. Praise ye the God of gods: for His mercy

endureth forever.” Likewise Ps. 117: “Give praise to the Lord, for

He is good.”

How is this mercy, principle of all the works

of God, reconcilable with the divine permission of evil and of the

final impenitence of many? Why does it sometimes raise up the

sinner, but not always? Therein lies a mystery surpassing the

natural powers of any intelligence created or capable of being

created, and beyond them not only because of its essential

supernaturalness, as in the case of the Trinity, but also by the

contingency resulting from dependence on the sovereign liberty of

God:

“If efficacious grace is refused to many,” says St. Thomas following

St. Augustine, “it is in justice, as the result of a sin [permitted,

of course, by God, but of which He was in no sense the cause]; if

this same grace is granted to others, it is out of mercy.”

It is fitting that these two divine perfections should be

manifested, as St. Paul declares;

there is consequently involved here the cooperation of

infinite justice, infinite mercy, and also of supreme liberty,

eminently wise in its good pleasure, which is in no way a caprice.

Obviously each of these divine perfections herein involved exceeds

the natural powers of any intelligence created or capable of being

created. None among them may be limited, just as in the mystery of

the Cross and Passion of the Savior neither infinite justice nor

infinite mercy may be restricted; they are reconciled in the

uncreated love of God and in the love of Christ delivered up for our

sake. The apparently contradictory aspects of a mystery must not be

restricted for the sake of a better understanding of them. Rather

must one, as it were, soar above this apparent contradiction by the

contemplation of faith. This is why St. Paul exclaims: “O the depth

of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How

incomprehensible are His judgments, and how unsearchable His ways!”

(Rom. 11:33.)

To acknowledge this mystery which is at the

topmost point of the peak we have just been describing, of that

summit which can never be seen from here below, one must cling to it

in pure faith, as Holy Scripture frequently urges us to do. Let us

recall, for example, the hymn of thanksgiving uttered by the elder

Tobias (Tob 13): “Thou art great, O Lord, forever, and Thy kingdom

is unto all ages. For Thou scourgest and Thou savest: Thou leadest

down to hell, and bringest up again: and there is none that can

escape Thy hand. . . . There is no other almighty God besides Him.

He hath chastised us for our iniquities: and He will save us for His

own mercy. See then what He hath done with us, and with fear and

trembling give ye glory to Him: and extol the eternal King of worlds

in your works.”

Theology, as the Council of the Vatican

asserts,

is essentially ordained to the contemplation of revealed

mysteries; infused faith, entirely divine and essentially

supernatural, is, in spite of its obscurity, eminently superior to

it, especially faith which is enlightened by the gifts of wisdom and

understanding. It becomes increasingly evident, then, that this

obscurity does not derive from absurdity or incoherence, but from a

light too intense for our feeble gaze. We begin to realize that,

with reference to these great mysteries of predestination, of grace,

and also of the will for universal salvation, we should read above

all the great theologians who were at the same time great

contemplative.

We come to understand better and better why, in the passive

purification of the soul described by the great spiritual writers,

St. John of the Cross in particular, the light of the gift of

understanding removes little by little the false lucidity of

eclectic combinations which stop halfway, and set the soul in the

presence of the real mystery without diminishing its sublimity. We

finally grasp the reason for St. Theresa’s remark: “The more obscure

a mystery is the more devotion I have to it,” obscure, that is, with

the translucent darkness which gives us a presentiment of the very

object of the contemplation of the blessed. Above all, we attain to

a growing realization of the fact that what is most obscure in these

mysteries is what is most divine, most elevated, most lovable; and

if we cannot yet cling to them in vision, we do so by faith and by

love.

The mystery involved here, whence proceeds the

principle of the origin of superiority to which this principle

leads, is the incomprehensible mystery of the love of predilection

in God. “No created being would be better than another were it not

better loved by God” (Ia, q. 20, a.

3); “What hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:7); “He

[God] chose us in Him [Christ] before the foundation of the world,

that we should be holy and unspotted in His sight in charity.

Who hath predestinated us unto the adoption of children through

Jesus Christ unto Himself: according to the purpose of His will:

unto the praise of the glory of His grace, in which He hath graced

us in His beloved Son” (Eph. 1:4-6). We can understand that these

words, “unto the praise of the glory of His grace,” ought to become

the delight of contemplatives, expressing as they do with

extraordinary splendor the principle of predilection which

manifestly dominates all the problems of sanctifying and actual

grace in every degree.

II. THE ULTIMATE BASIS OF THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN SUFFICIENT AND

EFFICACIOUS GRACE

(By way of

recapitulation, we here reprint this article which appeared in

French in the Revue Thomiste, May, 1937.)

“Whatsoever

the Lord pleased He hath done” (Ps. 134:6). “God does not command

the impossible” (St. Augustine and Council of Trent, Sess. VI, chap.

II).

We dealt with

this subject in a book which appeared in 1936: La prédestination

des saints et la grâce; cf. especially pp. 257-64; 341-50;

141-44. In the present article we wish to stress a higher principle

admitted by all theologians wherein the Thomists find the ultimate

basis of the distinction between sufficient and efficacious grace.

The problem. It is certain from

revelation that many actual graces bestowed by God do not produce

the effect (or at least the entire effect) toward which they are

ordered, whereas others do. The former are called sufficient and

purely sufficient; they confer the power of doing good without

carrying over efficaciously to the act itself. Man resists their

attraction; but their existence is absolutely certain, regardless of

what the Jansenists maintain. Otherwise God would command the

impossible, which would be contrary to His mercy and His justice.

Sin, moreover, would be inevitable; hence it would no longer really

be sin and consequently could not be justly punished by God. In this

sense we say that Judas, before sinning, could really, at the time

and place, have avoided the crime he committed; the same is also

true of the unrepentant thief before he expired beside our Lord.

The other actual graces which are termed

efficacious not only convey the real power of observing the

commandments; they cause us to observe them in fact, as in the case

of the good thief in contrast with the other. The existence of

efficacious actual grace is affirmed in numerous passages of

Scripture, such as: “I will give you a new heart, and put a new

spirit within you: and I will take away the stony heart out of your

flesh, and will give you a heart of flesh. And I will put My spirit

in the midst of you: and I will cause you to walk in My

commandments, and to keep My judgments, and do them” (Ezech. 36:26

f.); “Whatsoever the Lord pleased He hath done” (Ps. 134:6), that

is, all that He wills, not conditionally but absolutely, He

accomplishes even the free conversion of man, as in the case of King

Assuerus at the prayer of Esther (Esther 13:9; 14:13); “And God

changed the king’s spirit into mildness” (ibid., 15:11). The

infallibility and efficacy of a decree of God’s will are obviously

based in these texts upon His omnipotence and not upon the foreseen

consent of King Assuerus. In the same sense the Book of Proverbs

declares (21:1): “As the divisions of waters, so the heart of the

king is in the hand of the Lord: whithersoever He will He shall turn

it”; likewise Ecclus. 33:24-27. Jesus Himself declares: “My sheep

hear My voice: and I know them, and they follow Me. And I give them

life everlasting: and they shall not perish forever, and no man

shall pluck them out of My hand” (John 10:27); and again: “Those

whom Thou gavest Me have I kept; and none of them is lost, but the

son of perdition, that the scripture may be fulfilled’’ (ibid.,

17:12). St. Paul writes with the same purport to the Philippians

(2:13): “For it is God who works in you, both to will and to

accomplish, according to His good will.”

The Second Council of Orange, opposing the

Semi-Pelagians, quotes several of these scriptural texts and refers

to the efficacy of grace in the following terms (Denz., no. 182):

“Whatever good we do, God works in us and with us so that we may

work.” There is therefore a grace which not only gives the real

power of doing good (which exists in one who sins), but which is

effectual in the act, although it does not exclude our free

cooperation but arouses and induces it in us. St. Augustine explains

these same scriptural texts when he says: “God converts and

transforms the heart of the king . . . from wrath into mildness by

His most secret and efficacious power” (I ad Bonifatium,

chap. 20).

Hence a great

majority of the ancient theologians, Augustinians, Thomists,

Scotists, have allowed that the grace termed efficacious is so of

itself, because God wills it and not because we will it by a consent

foreseen in the divine prevision. God is not merely the spectator of

what distinguishes the just man from the sinner; He is the author of

salvation. It is true that these ancient theologians are divided on

the secondary question of explaining how grace is efficacious of

itself; some have recourse to the divine motion known as physical

premotion, others to a predominating delight or some similar

attraction. But all admit that the grace called efficacious is so of

itself.

Molina, on

the contrary, maintained that it is extrinsically efficacious on

account of our consent which was foreseen by God through mediate

knowledge. This mediate knowledge has always been rejected by

Thomists who accuse it of attributing passivity to God with respect

to our free determinations (possible in the future, and then future)

and of leading to determinism regarding circumstances (so far as, by

examining these, God would foresee infallibly what a man would

choose). Thus the very being and the goodness of man’s free and

salutary choice would derive from him and not from God, at least in

the sense in which Molina writes: “It may happen that, with equal

help, one of those called will be converted and not the other.

Indeed, even with less help one man may rise while another with

greater help does not, but perseveres in his obduracy.”

The opponents of Molinism reply that there

would thus be a good, that of salutary free choice, which would not

proceed from God, the source of all good. How then can the words of

Jesus be sustained (John 15:5): “Without Me you can do nothing” in

the order of salvation, and those words of St. Paul: “For who

distinguisheth thee? Or what hast thou that thou hast not received?

And if thou hast received, why dost thou glory, as if thou hadst not

received it?” (I Cor. 4:7.) It would in fact come to pass that of

two sinners placed in the same circumstances and equally aided by

God, one would be converted and not the other; man would distinguish

himself and become better than another without greater assistance

from God, without having received more, contrary to the text of St.

Paul.

The Molinists

do not fail to press the question further: If in order to act

effectually one requires, in addition to sufficient grace, a grace

which is efficacious of itself, does the former truly convey a real

power of acting? It does so, the Thomists reply, if it is true that

a real power of acting is distinct from the action itself; if it is

true, as Aristotle maintained against the Megarians, that an

architect who is not actually building still has the real power to

do so; if it is true that a man who is asleep still has a real power

of seeing: from the fact that he is not exercising his sight at the

moment it does not follow that he is blind, Moreover, if a sinner

did not resist sufficient grace, he would receive the efficacious

grace proferred in the former, as the fruit is in the flower. If he

refuses, he deserves to be deprived of this further help.

Our

adversaries insist that St. Thomas himself did not distinguish

explicitly between grace efficacious of itself and grace which

merely conveys the power of doing good. It is an easy matter to cite

many texts of the Angelic Doctor wherein he makes this distinction;

for instance: “The help of God is twofold: God gives a faculty by

infusing power and grace through which man is made able and apt to

operate. But He confers the very operation itself inasmuch as He

works in us interiorly moving and urging us to good, . . . according

as His power works in us both to will and to accomplish according to

His good will” (In Ep. ad Ephes., chap. 3, lect. 2);

likewise, Ia IIae, q. 109, a. I, a. 2, a. g, 10; q. 113, a. 7, 10,

and elsewhere. He also writes: “Christ is the propitiation for our

sins, for some efficaciously, for all sufficiently, since the price

of His blood is sufficient for the sal-vation of all, but possesses

efficacy only in the elect, on account of an impediment” (In Ep.

ad Tim., 2:6). God often removes this impediment, but not

always. Therein lies the mystery. “God deprives no one of what is

his due” (Ia, q. 23, a. 5 ad 3); “He gives sufficient help to avoid

sin” (Ia IIae, q. 106, a. 2 ad 2). As for efficacious grace, “if it

is given to one sinner, that is through mercy; if it is denied to

another, that is in justice” (IIa IIae, q. 2, a. 5 ad I) .

Thomists

analyze these texts as follows: Every actual grace which is

efficacious of itself with regard to an imperfect salutary act such

as attrition, is sufficient with regard to a more perfect salutary

act such as contrition.

This is manifestly the sense of St. Thomas’ doctrine, and, according

to him, if a man actually resists the grace which confers the power

of doing good, he deserves to be deprived of that which would

effectually cause him to do good.