| Grace: Commentary on the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas, Chapter Two |

| Rev. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P.

|

|

QUESTION 109 THE NECESSITY OF GRACE In this question there are ten articles, methodically arranged in progressive order, beginning with the lesser actions for which grace is necessary (for example, knowing some truth) and ending with the last supreme good work, that is, final perseverance. (Cf. titles.) There are three parts, as Cajetan observes at the beginning of article 7:

ARTICLE I. WHETHER WITHOUT GRACE MAN CAN KNOW ANY TRUTH Statement of the question. It seems that grace is required for knowing any truth whatever, for it is said in II Cor. 35: “Not that we are sufficient to think anything of ourselves as of ourselves.” And St. Augustine maintained this answer in a certain prayer, but he himself retracted later (Retract., I, 4), as is said in the argument to the contrary and declared that it could be refuted thus: “Many who are not sinless know many truths,” for example, those of geometry. The first conclusion is the following. To know any truth, man requires at least natural help from God, but he does not require a new supernatural illumination for it. The aforesaid natural help is due to human nature as a whole, but not to any individual. Proof of the first part. Since every created agent requires divine premotion in order to pass from potency to act, “however perfect the nature of any corporal or spiritual being, it cannot proceed to act unless moved by God.”1 Proof of the second part. Because many truths do not surpass the power proper to our intellect, they are easily knowable naturally (cf. ad 1, ad 2, ad 3). It should be noted that the natural concurrence called here by St. Thomas “motion” (motio) is not mere simultaneous cooperation.2 Likewise, contrary to Suarez, the virtual act of the will cannot, without divine motion, be reduced to a secondary act, for St. Thomas said: “However . . . (cf. Suarez, Disp. met., disp. 29, sect. I, no. 7, on virtual act). We reply: there is more in the secondary act than in the virtual act, which in reality differs from the action, nor is it its own action. Already in this first article it is evident that St. Thomas withdraws nothing from divine motion. The second conclusion is the following. For attaining a knowledge of supernatural truths, our intellect stands in need not only of the natural concurrence of God, but of a special illumination, namely, the light of faith or the light of prophecy and of a proportionate motion. The reason is that these truths surpass the power proper to our intellect. OBJECTIONS Objection to the first conclusion. Vasquez presents several objections in the first place, he says: The intellect, indifferent to truth and falsehood, is determined by grace toward any truth. But our intellect is indifferent to truth and falsehood. Therefore our intellect is determined by grace toward any truth. Reply. I distinguish the major: by grace, broadly speaking, granted; properly, denied. Let the minor pass, although the intellect is not so indifferent to truth and falsehood as not to incline naturally to truth. It is called grace broadly since, for example, it is given to Aristotle rather than to Epicurus. I insist. Grace properly speaking, is required in this case, at least after original sin, according to the fideists, such as Bautin, Bonetti. Grace, properly speaking, is required that the wounded intellect may be healed. But when it knows any truth, our intellect is at least partially healed. Therefore grace, properly speaking, is required for knowing any truth. Reply. I distinguish the major: for knowing the whole body of natural truths, I concede; for any one truth, I deny. The intellect would thus be not merely darkened but extinct, were it incapable of knowing even the least truth without healing grace. Let the minor pass. I distinguish the conclusion in the same way as the major- I say transeat in regard to the minor but I do not concede since the intellect is not properly healed when it knows a truth of geometry but rather when it knows the truth of natural religion. Instance: But the intellect is extinct or almost extinct, according to the Jansenists. Ignorance is opposed to knowledge as being a total deprivation. But the wound of ignorance is in the intellect, according to tradition. Therefore. Reply. I distinguish the major: total ignorance, granted; partial ignorance, denied. I contradistinguish the minor; explanation: the wound of ignorance affects principally the practical intellect wherein prudence resides; but there remains in the practical intellect a synderesis, and the speculative intellect is less wounded, since it does not presuppose rectitude of the appetites. Objection to the second conclusion. Whatever does not surpass the object of our intellect can be known without grace. The mysteries of faith do not surpass the object of our intellect. Therefore. Reply. I distinguish the major: a proportionate object, granted; an adequate object, surpassing a proportionate object, denied. I contradistinguish the minor. I insist. But the mysteries of faith do not surpass the proportionate object. That which is known habitually to the senses does not surpass the proportionate object. But the mysteries of faith are known habitually to the senses. Therefore. Reply. I distinguish the major: whatever is so known without revelation, granted; after revelation, I distinguish further: they do not surpass the remotely proportionate object, granted; proximately proportionate, denied. I insist. But at least, after external revelation, the mysteries of the faith do not surpass the proximately proportionate object. That which is known by its species abstracted from the senses and through external signs does not surpass the proximately proportionate object. But the mysteries of faith are thus known. Therefore. Reply. I distinguish the major: if this is known from a human motive, granted; and then it does not require supernatural grace; and contrariwise if it is known from a supernatural motive, that is, on the authority of God revealing in the order of grace (cf. below, Corollary 4). I insist. But man is made in the image of the Trinity. And he is naturally capable of knowing this image. Therefore. Reply. I distinguish the minor: so far as man is the image of God, the author of nature, granted; so far as he is the image of the Trinity, denied, since the term of this relationship is of a higher order. Thus if someone is given an image of an entirely unknown man, he cannot say whose image it is. (For a correct treatment, cf. Salmanticenses, De gratia, disp. III, dub. IV, no. 40, and Billuart, De gratia, diss. III, a. 2). Thomists have drawn several corollaries from this article, using more modern terminology. Corollary 1. Fallen man, without grace, with natural concurrence alone, is capable of knowing certain natural truths, namely, the first speculative and practical principles of reason and the conclusions which are easily drawn from them. This is contrary to some ancient writers who do not distinguish sufficiently between grace and natural concurrence; it is also contrary to Vasquez who, following the ways of the nominalists, disparaged the powers of reason excessively, as did Baius and the Jansenists, Quesnel and the nineteenth-century fideists, such as Bautin and Bonetty. With regard to this conclusion, cf. the following condemned propositions. Denz., no. 1022. This one of Baius is condemned: “Those who consider, with Pelagius, the text of the Apostle to the Romans (2:14): ‘The Gentiles, who have not the (written) law, do by nature those things that are of the law,’ understand it to apply to the Gentiles who have not the grace of faith.” For it is certainly contrary to Baius that, without grace, man by natural reason can know the first precepts of the natural law: good ought to be done, thou shalt not kill. Denz., no. 1391. This proposition of Quesnel is condemned: “All knowledge of God, even natural, even in pagan philosophy, can come only from God, and without grace it produces nothing but presumption, vanity, and opposition to God Himself, in place of sentiments of adoration, gratitude, and love.” Thus had spoken previously Luther and Calvin (I De Inst., chaps. 1 and 2), as if peripatetic philosophy had come from diabolic inspiration. The natural reason of Aristotle was capable of discovering the theory of potency and act, of the four causes, and this without any opposition to God. Denz., no. 1627. The following may probably be attributed to Bautin: Although reason is obscure and weak through original sin, there still remains in it enough lucidity and power to lead us with certainty to (the knowledge of) the existence of God, to the revelation made to the Jews by Moses and to the Christians by our adorable God-man.”The Vatican Council defined the following (Denz., no. 1806): “If anyone says that the one true God, our Creator and Lord, cannot certainly be known by the light of natural human reason, let him be anathema.” This is contrary to the traditionalists, Kant, and the Positivists. Finally, in the oath against Modernism: “I acknowledge in the first place and of a truth, that, by the light of natural reason through the things which have been made, that is, through the visible works of creation, God, the beginning and end of all things, can be certainly known and even demonstrated.” Likewise in regard to miracles confirming the Gospel it is similarly declared that they are “most certain signs that the Christian religion is of divine origin . . . and even in the present time especially adapted to the intelligence of all men.” Moreover, the reason for this conclusion is the one given in the article, that is: Every power infused in created things is efficacious in respect to its own proper effect. But our intellect is a power infused into us by God and, granted that it is darkened by sin, yet it is not extinct. Therefore it can of itself, with natural concurrence, arrive at a knowledge of certain natural truths. Otherwise intellectual power would be, in its own order, much more imperfect than are the powers of bodies, of plants and animals,in respect to their own objects, sight and hearing, for example. As a matter of fact, the natural concurrence required for the knowledge of any truth may be called grace in the broad sense, inasmuch as it is not due to any individual but to human nature in general; (cf.Ia, q. 21, a. I ad 3): “It is due to any created thing that it should have that which is ordained to it, as to a man that he have hands and that the other animals serve him; and thus again God works justice when He gives to anything that which is due to it by reason of its nature and condition.” God owes it to Himself to give to the various kinds of plants and animals and to humankind the natural concurrence enabling them to reach their final end on account of which they were made. But, on the other hand, it is not to be wondered at that what is deficient should sometimes fail, and God is not bound to preventthese defects, since, if He prevented them all, greater goods would not come about, and it is on account of these many goods that He permits the defect. Hence, as our intellect is defective, there is due to it, according to the laws of ordinary providence, that it should atleast sometimes be moved toward the truth and not always fall into error. But the fact that Aristotle, for example, rather than another, let us say Epicurus, may be moved in the direction of truth, this is not due to him; it is by a special providence and benevolence, and in this sense such natural concurrence is called “grace” broadly speaking. And it is proper to pray that one may obtain this grace in the wide sense of the term. Corollary 2. Fallen man, without a special added grace, cannot, at least with any moral power, know either collectively or even separately all natural truths, speculative or speculative-practical, or, for still greater reason, practical-practical; since for these last, as for prudence, rectitude of the appetite is required. Many hold, not without probability, that without special grace man can know all natural speculative truths, by physical power, since these truths do not exceed the capacity of a man possessing a keen mind. But in the present corollary it is a question of moral power, that is, such as may be rendered active without very great difficulty. And it is certain that this moral power is not given in regard to all the aforesaid kinds of truth taken together. Rather, it was on this account that the Vatican Council declared (Denz., no. 1786) revelation to be morally necessary “so that those things concerning divine matters which are not of themselves impenetrable to human reason may nevertheless, in the present condition of the human race, be readily known by all with a firm certainty and no admixture of error.” This is explained by St.Thomas (Ia, q. I, a. I; IIa IIae, q. 2, a. 3 and 4; Contra Gentes, Bk.I, chaps. 4 and 6; Bk. IV, Gentes, chap. 52). For the impediments are manifold: the shortness of life, the weakness of the body, domestic cares, the disorder of the passions, etc. It is clearly evident that, with all these impediments, fallen man without grace has not the moral power to attain to the knowledge of all natural truths together; nor even, as a matter of fact to the separate knowledge of them: 1. Because the wound of ignorance is in the intellect, preventing especially thatease of understanding necessary to prudence, for prudence presupposes rectitude of the appetite; 2. because many speculative natural truths are very difficult, demanding long and rigorous study for a certain and complete knowledge of them and therefore a constantly good will, burning love of truth, a relish for contemplation, undisturbed passions, a good disposition of the senses, leisure uninterrupted by cares. All of this cannot be arrived at easily before regeneration by healing grace; indeed even afterward a special grace is required for it. Among natural truths, according to Billuart, there are some so extremely difficult that no man has thus far been able to attain a certain knowledge of them, for example, the ebb and flow of the tides, the essence of light, electricity, magnetism, the inner development of the embryo; similarly, the inner nature of sensation, the active intellect and its functioning, the intimate relationship between the last practical judgment and choice, etc.; likewise the reconciling of the attributes of God as naturally knowable, although the knowledge of the existence of God, supreme Ruler, is easily arrived at by common sense from the order of the universe. Doubt. Whether this special grace required for a knowledge of all these natural truths is properly supernatural. Reply. It suffices that it is supernatural in respect to the manner of which is supernatural in respect to its substance, because the knowledge of which we are speaking is ontologically natural. Corollary 3. Supposing the existence of an external revelation, fallen man, with natural, general concurrence alone and without a special added grace, is able to know and enlarge on supernatural truths, from some human or natural reason. Thus the demons believe naturally, by a faith not infused but acquired, on the evidence of compelling miracles, as is demonstrated in IIa IIae, q. 5, a. 2. And formal heretics retain certain supernatural truths, not from the supernatural motive of divine revelation (otherwise they would believe all that is revealed), but from a human motive, that is, on the bases of their own judgment and will; for example, because they consider this faith to be honorable or useful to themselves, or because it seems to them very foolish to deny certain things in the Gospel. The reason for this is that, although a true supernatural is in itself entitatively supernatural, yet, as depending upon a human or natural motive, it is not formally supernatural. Why? Because an object, not as a thing, but by reason of object, is formally constituted by the formal motive through which it is attained. Thus when a formal heretic from a human motive and by human faith believes in the Incarnation, while rejecting the Trinity; then the object believed, as a thing, is supernatural, but, as an object, it is not supernatural. Therefore it may thus be attained by the natural powers, and then the supernatural truth is attained only materially because it is not attained formally in its supernaturalness, as it is supernatural. That a demon should naturally believe the mysteries of faith is analogical, all proportions being maintained, to a dog’s materially hearing human speech as sound but not really hearing formally the intelligible meaning of this same speech. Similarly, “the sensual man (for example, a heretic retaining certain mysteries of faith) perceiveth not these things that are of the Spirit of God; for it is foolishness to him, and he cannot understand” (I Cor. 2:14); cf. also St. Thomas’ Commentary on this Epistle. We might draw another comparison with the case of one who listens to a symphony of Beethoven or Bach, possessed of the sense of hearing but devoid of any musical sense; he would not attain to the spirit of the symphony (cf. our De revelatione, I, 478, based on IIa IIae, q. 5, a. 3). Corollary 4. Man cannot believe supernatural truths from the supernatural motive of divine revelation without a special interior grace, both in the intellect and in the will. This is contrary, first, to the Pelagians, who say that external revelation is sufficient for the assent of faith (cf. Denz., nos. 129 ff.) and, secondly, to the Semi-Pelagians, who would have it that the beginning of faith comes from us (cf. Denz., nos. 174 ff.; Council of Orange, c. 5, 6, 7); therein it is declared that the inspiration and enlightenment of the Holy Spirit is required in this matter (Denz., nos. 178-80). These definitions of the Church are based upon several texts of Sacred Scripture cited by the Council of Orange, for example, Ephes. 2:8: “for by grace you are saved through faith, and that not of yourselves, for it is the gift of God; not of works, that no man may glory.” This does not refer to external revelation, for it is further said in the same Epistle (1:17 f.): “That . . . God . . . may give unto you the spirit of wisdom and of revelation, in the knowledge of Him: the eyes of your heart enlightened, that you may know what the hope is of his calling”; and (Acts 16:14): “ . . . Lydia . . . whose heart the Lord opened to attend to those things which were said by Paul.” Again, this fourth corollary is opposed to Molina and many Molinists who declare that fallen man can, without supernatural grace, believe supernatural truths from a supernatural motive, but then he does not believe as is necessary for salvation, for which grace is required. And therefore Molina holds that the assent of faith is supernatural not in respect to substance by virtue of its formal motive, but only in respect to mode, by reason of the eliciting principle and by reason of its extrinsic end. (Cf. Concordia, q. 14, a. 13, disp. 38, pp. 213 ff., and our De revelatione, I, 489, where Molina and Father Ledochowski are quoted.) This question has been treated at length and fully by the Salmanticenses in their Commentary on our article, De gratia, disp. III, dub. III, and I have quoted their principal texts in De revelatione, I, 494, 496, showing that therein they are in accord with all Thomists from Capreolus to the present day (pp. 458-514). Their conclusions, here cited, ought to be read. The argument put forth against Molina and his disciples is found in IIa IIae, q. 6, a. I, “Whether faith is infused in man by God”: “For, since man, assenting to the things which are of faith, is raised above his nature, it is necessary that this be instilled into him by a supernatural principle impelling him interiorly through grace,” for an act is specified by its formal object (objectum formale quo et quod); if, therefore, the latter is supernatural, the act specified by it is essentially supernatural and cannot be elicited without grace. Further, St. Thomas affirms this to be true even of faith lacking form (informus), that is, faith without charity (IIa IIae, q. 6, a. 2); even faith lacking form is a gift of God, since it is said to lack form on account of a defect of extrinsic form, and not on account of a defect in the specific nature of infused faith itself, for it has the same specifying formal object. Thus Billuart comments on our article: “the formally supernatural object as such cannot be attained except by a supernatural act. This upsets the basic assertion of Molina, who maintains that the assent to faith from the motive of divine revelation is natural in respect to its substance, and supernatural in respect to its mode. . . . This opinion does not seem to us sufficiently removed from the error of the Semi-Pelagians.” (Likewise, the Salmanticenses, loc. cit.) Confirmation. The Council of Orange (c. 5,6,7; Denz., nos. 178-80) defined grace to be necessary for the initial step toward faith and for the belief necessary to salvation. But to believe on account of the formal supernatural motive of infused faith itself is already to believe in the way necessary to salvation; what more formal belief can then be required? Therefore, to believe on account of this supernatural motive is impossible without grace. Many difficulties would arise from any other opinion. 1. An act cannot be specified by an eliciting principle, for this eliciting principle itself requires specifying, and it is specified by the act toward which it tends, as the act is specified by its object. Otherwise specification would come from the rear rather than from thefront, as if the way from the College “Angelicum” to the Vatican were specified by the terminus from which, and not by the terminus toward which. 2. An act of faith would be no more supernatural than an act of acquired temperance ordered by charity to a supernatural end; it would be less supernatural than an act of infused temperance, as referred to by St. Thomas (Ia IIae, q. 63, a. 4). This supernatural in respect to mode is the supernatural almost as applied from without, like gold applied over silver for those who cannot afford to buy pure gold jewelry: it is “plated,” “veneered.” 3. What Molina says of the act of theological faith, could equally be said of the act of hope, and even of the act of charity, for the substance of which natural good will would sufice, and the supernatural mode would be added to make it what is required for salvation. But then the charity of the viator thus specified by a formal object naturally attainable would not be the same as the charity of the blessed, which must be, like the beatific vision, essentially supernatural. Hence charity would be something different in heaven from what it is now, contrary to the words of St. Paul, “charity never falleth away” (I Cor. 13:8). Thus even Suarez vigorously opposes Molina in this matter. There would be innumerable other consequences as indicated in De revelatione, I, 511-14. We cannot therefore admit the following two theses of Cardinal Billot on the subject as put forward in his book, De virtutibus infusis (71, 87, 88): “Supernatural formality, causing acts to be proportioned to the condition of objects conformable to themselves, does not proceed from the object in that it performs in respect to us the office of an object, nor, namely, either from the material object which is believed, hoped, or loved, or from the formal object on account of which it is believed, hoped, or loved, but solely from the principle of grace by which the operative faculty is elevated.” “Supernatural habits are not necessarily distinguished from natural habits according to their objects” (p. 84). In opposition to our thesis, cf. the objections in De revelatione, I, 504-11. The principal one is the following. The demons believe (Jas. 2), and they believe without grace. But they believe from the motive of divine revelation. Therefore grace is not necessary to believe from a motive of divine revelation. Reply.

I concede the major. I distinguish the minor: that the demons believe

formally from the motive of divine revelation according as it is

supernatural in respect to substance in itself and on that account, I

deny; that they believe materially on the evidence of the signs of

revelation, I grant; to this evidence their faith is ultimately

reducible. (Cf. IIa IIae, q. 5, a. 2 ad I, 3.) They believe, says

St.Thomas, as it were under constraint from the evidence of miracles,

for it would be exceedingly stupid for them to reject this evidence.

They therefore attain to God the author of nature and of miracles, but

not really to God the author of grace, nor to revelation as it proceeds

from God the author of grace. On the contrary, revelation as proceeding

from God, the author of grace, specifies infused faith which is of a

higher species than would be a faith, supernatural in respect to mode,

based upon the revelation of God, author of nature. (Cf. Salmanticenses

quoted in De revelatione, I, 496,471.) ARTICLE II.

WHETHER MAN CAN WILL TO DO ANY State of the question. It seems that man can do some good without grace: 1. for his acts are in his power, since he is ruler of his acts; 2. for everyone can do better that which pertains to him by nature than that which is beyond him by nature; but man can sin by himself, which is acting beyond and even against nature; therefore with even greater reason can he do good of himself. This objection raises the question whether not sinning, or persevering in good, is itself a gift of God; whether of two men, equally tempted and equally assisted, it can happen that one sins and the other does not. 3. Just as our intellect can, of itself, know truth, so our will can, of itself, will the good. This question concerns: 1. a morally or ethically good work in the natural order (such as proceeds from the dictates of right reason and is not vitiated by any circumstances) so that it is not a sin; and 2. good works conducive to salvation, such as are ordained to a supernatural end, not indeed always as meritorious acts presupposing habitual grace, but as salutary acts disposing to justification and presupposing actual grace. Reply. In respect to these two problems, certain truths are articles of faith. 1. It is of faith that not all the works of infidels or sinners are sins (against Wyclif, Denz., no. 606; John Hus, no. 642, Baius, nos. 1008, 1027 ff .; Quesnel, nos. 1351, 1372, 1388) Therefore without the grace of faith a man can do some morally or ethically good works. 2. It is of faith that supernatural good cannot be effected by fallen man without grace. Cf. Council of Orange (Denz., no. 174), can. 6, 7, 9, 11, 12-20, 22; and Council of Quierzy (Denz., no. 317), c. 2. These two articles of faith are based on many passages in Holy Scripture. 1. Holy Scripture does indeed praise certain works of infidels and testifies that they were rewarded by God; for example, it praises the kind-heartedness of the Egyptian midwives who did not wish to kill the children of the Hebrews in conformity with the iniquitous command of Pharaoh (Exod., chap. I); the hospitality of Rahab the harlot, who refused to betray the men sent by Josue (Josue, chap. 2), is also praised; likewise God gave the land of Egypt to King Nabuchodonosor, that he might wage a successful war against the inhabitants of Tyre, according to the command of God (Ezech. 29:20). St. Augustine says (De civ. Dei, Bk. V, chap. 15) that God granted a vast empire to the Romans as a temporal reward of their virtues and good works. But God neither praises nor rewards sins, but rather punishes. Therefore. Similarly it is said in Romans (2:14): “The Gentiles, who have not the law, do by nature those things that are of the law”; in other words, they do at least some good works, as St. Augustine shows (De spiritu et littera, chap. 27). 2. The other proposition of faith, that supernatural good works cannot be performed by fallen man without grace, is also based on many texts from Scripture cited by the Council of Orange: “A man cannot receive anything, unless it be given him from heaven” (John 3:27). “This is the work of God, that you believe in Him whom He hath sent” (John 6:29). “Without Me you can do nothing” (John 15:5). “I am the vine; you the branches” (ibid.). “It is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth, but of God that showeth mercy” (Rom. 9:16). “It is God who worketh in you, both to will and to accomplish, according to His good will” (Phil. 2:13). “What hast thou that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:7.) “No man can say the Lord Jesus, but by the Holy Ghost” (I Cor. 12:3). “Not that we are sufficient to think anything of ourselves, as of ourselves: but our sufficiency is from God” (II Cor. 3 5 ). “Every best gift, and every perfect gift, is from above, coming down from the Father of lights” (Jas. 1:17). There are innumerable texts from St. Augustine; for example, the one quoted in the Sed contra. In the body of the article are found four conclusions, which should be consulted in the text itself. 1. To accomplish any good whatever, man, in any state, requires the general concurrence of God, whether in the state of incorrupt or of corrupt nature (or even in the state of pure nature of which St. Thomas does not speak here, but the possibility of which he admits, as stated in II Sent., d. 31, q. I, a. 2 ad 3, and Ia, q. 95, a. I). The reason for this is that every creature, since it neither exists nor acts of itself, is in potency regarding action, and needs to be moved from without that it may act, as said in article I. This efficacious concurrence toward a naturally virtuous good is due, as we have said, to human nature in general, not to any individual, in whom God may permit sin. 2. In the state of integral nature, man did not require special added grace, except for performing supernatural works, not, that is, for morally good works commensurate with nature. For nature was then in a perfect state and needed only general concurrence, which is, of course, to be understood in the sense of a concurrence which is prior and efficacious in itself, not in the sense accepted by Molina. 3. In the state of fallen nature man requires supernatural grace not only to perform a supernatural work, but to observe the whole natural law (as will be made more evident later in article 5). 4. Fallen man can do some morally good work in the natural order with general concurrence alone, for example, build houses, plant vineyards, and other things of this kind; and he can do this on account of a duly virtuous end, so that this act may be ethically good from the standpoint of its object, its end, and all its circumstances; for instance, that a man build a home for the good of his family, that is, in such a way that there is no sin involved. This is particularly evident from the fact that, for St. Thomas, there are no indifferent acts in regard to an individual (Ia IIae, q. 18, a. 9; cf. above, Ia IIae, 65, a. 2): “Acquired virtues, according as they are operative of good ordained to an end which does not exceed the natural faculty of man, can be deprived of charity,” but they are so on the part of the subject in the circumstance of his disposition, not in the circumstance of a virtue difficult to set in motion, nor closely connected actually. Thus not all the works of infidels and sinners are sins. The reason is that, since human nature “is not totally corrupted” by sin so as to be entirely deprived of natural good, therefore it can, through the power which remains, easily do some morally good works with general concurrence, just as a sick man may have some power of movement in himself, although he is not able to move perfectly unless he is cured. REFUTATION OF OBJECTIONS (cf. De veritate, q. 24, a. 14) First objection. That is in the power of a man of which he is master. But a man is master of his acts. Therefore it is in the power of a man to do good. Reply. I distinguish the major: without the concurrence of God, denied; with the concurrence of God, granted. I grant the minor. I distinguish the conclusion in the same way as the major. (Read St. Thomas’ answer.) Second objection. Everyone can do better that which pertains to him by nature than that which is beyond his nature. But man can sin of himself, which is beyond nature. Therefore man can do good of himself. (See a similar objection in De veritate, q. 24, a. 14, objections 3 and 4, also objection 2 and the body of the article toward the end.) Likewise some say that of two men, tempted in the same way and equally assisted, it may be that one perseveres in attrition or in an easy, imperfect prayer, whereas the other, on the contrary, sins by not continuing this easy act. St. Thomas’ reply to objection 2 is as follows: “Every created thing needs to be preserved in the goodness proper to its nature by something else (that is, by God), for of itself it can fall away from goodness. At least, he who does not sin is divinely preserved in the goodness proper to his nature, while God does not preserve the other, but, on the contrary, permits sin in him; therefore they are not equally assisted. However, nature is not completely corrupt; it is able to do some good but with the help of God, which is due to nature in general, but not indeed to this individual. Therefore, as Augustine says, we ought to thank God inasmuch as we avoid sins which were possible to us, for the very fact of not sinning is a good coming from God; it is, in other words, being preserved in goodness. In reply to the third objection it is noted that “human nature is more corrupted by sin in regard to its appetite for the good than in regard to its knowledge of the truth.” This is because original sin first causes an aversion of the will directly from the final supernatural end, and indirectly from the final natural end; and consequently a disorder in the sensitive appetite tending toward sensible goods, not according to the dictates of right reason. Doubt. How is this general concurrence, necessary for fallen man to accomplish any moral good, to be understood? Reply. The Molinists understand it as a natural, general, indifferent concurrence which the will, through its own volition, directs toward the good. But the Thomists reply that in that case God, by moving one as far as the exercise of the will is concerned, would be no more the author of a good work than of a bad one (contrary to the Council of Trent, Denz., no. 816).3 Therefore they insist upon a prevenient, determining, and effective concurrence enabling a man to do good rather than evil. The early Thomists called this a special concurrence, a since it is not due to this or that individual; but later Thomists call it a general concurrence, because it is, in a certain sense, due to human nature, even in its fallen state, for nature is not totally corrupt or confirmed in evil, but only weakened. However, it is not due to one individual rather than to another, and from this aspect it is special. In the same way various texts from Scripture, the councils, the Fathers, and St. Thomas, which seem to be contradictory, are reconciled. For example: “No one has anything of himself but sin and lying,” says the Council of Orange (can. 22). That is to say, no one tells the truth with honest intent without at least the natural assistance of God, which is a grace, broadly speaking, with respect to this man on whom it is bestowed rather than on another; otherwise it would have the meaning which Baius gives to it when he says: “Man’s free will, without the grace and help of God, is of no use except to commit sin.” Baius means not only natural assistance, or grace broadly speaking, but grace in the proper sense, which comes from Christ, hence sanctifying grace and charity. ARTICLE III.

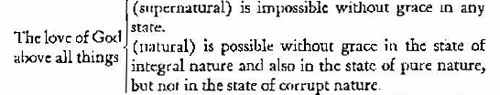

WHETHER MAN CAN LOVE GOD ABOVE We are especially concerned, in this article, with the love of God, author of nature, above all things, although there is still a reference in the reply to the first objection to the love of God, author of grace, which proceeds from infused charity. St. Thomas had already dealt with this subject (Ia, 4.60, a.5) in respect to the angels, and later (IIa IIae, q. 26, a. 3), where he distinguishes more explicitly between natural and supernatural love of God. (Likewise on I Cor., XIII, lect. 4; De virtutibus, q. 2, a. 2 ad 16; q. 4, a. I ad 9; Quodl. I, q. 4, a. 3.) In the statement of the question he sets down the objections to the possibility of a natural love of God above all things. Later, Baius and Jansen again voice the same objections. This natural love of God above all things seems impossible: 1. because loving God above all things is proper to the act of infused charity; 2. since no creature can rise above itself, it cannot naturally love God more than itself; 3. because, grace would be added to no purpose. Let us examine: 1. the doctrine of St. Thomas; 2. its confirmation by the condemnation of Baius and Quesnel; 3. the controversy of modern theologians on this subject. I. THE TEACHING OF ST. THOMAS This teaching can be reduced to three conclusions treating of1. the love of God, author of nature, above all things in the state of integral nature. 2. the love of God, author of nature, above all things in the state of corrupt nature. 3. the supernatural love of God, author of grace, above all things. We shall see later, in reference to a particular problem, whether man in the state of pure nature would be able to love God, author of nature, above all things. This question is not solved by the Sed contra, because in it the expression “by merely natural powers” does not refer to pure nature but to integral nature. The article itself should be read. Conclusion 1. In the state of integral nature, man did not require an added gift of grace to love God, the author of nature, above all things efficaciously; he required only the help of God moving him to it, or natural concurrence. This is proved as above, in regard to the angels, that is, in forms. Loving God, the author of nature, above all things is natural to man and to every creature, even irrational, in its own way; for, as the good of the part is for the sake of the good of the whole, every particular thing naturally loves its own good on account of the common good of the whole universe, which is God. But man in the state of integral nature could have performed, by virtue of his nature, the good which was natural to him. Therefore man in the state of integral nature could, by virtue of his nature without any added grace, efficaciously love God the author of nature above all things. The major is explained above (Ia, 60, a. 5) and later (IIa IIae, q. 26, a. 3). According to Ia, 60, a. 5: “The natural inclination in those things which are without reason throws some light upon the natural inclination in the will of the intellectual nature. But in natural things, everything which, as such, naturally belongs to another, is principally and more strongly inclined to that other to which it belongs than toward itself. For we observe that a (natural) part endangers itself naturally for the preservation of the whole, as the hand exposes itself without any deliberation to receive a blow for the safeguarding of the whole body. And since reason imitates nature, we find an imitation of this manner of acting in regard to political virtues. For it is the integral nature; corrupt nature; part of a virtuous citizen to expose himself to the danger of death for the safety of the whole nation. And if a man were a natural part of this state, this inclination would be natural to him. Since, therefore, the universal good is God Himself, and angels and men and all creatures are encompassed by this goodness, and since every creature naturally by its very being belongs to God, it follows that even by a natural love angels and men love God in greater measure and more fundamentally than they do themselves. Otherwise, if they naturally loved themselves more than God, it would follow that natural love was perverse and would not be perfected by charity but rather destroyed.” These last words imply that in the state of pure nature man would be able to love God naturally above all things, otherwise natural love would be perverse; but we shall see in the second conclusion that this is not so in the state of fallen nature on account of its wounds. The major of the present argument is entirely fundamental and a most beautiful concept. It is thus explained (Ia, q. 60, a. 5 ad I): “Every (natural) part naturally loves the whole more than itself. And every individual member naturally loves the good of its species more than its own individual good.” Hence onanism, preventing fertility, is a crime against nature, against the good of the species. A good Thomist, then, loves and defends the doctrine of St. Thomas more than his personal opinions. However, in the exposition of this major the excess of pantheism must be avoided, for then the creature would love God more than self naturally in such a way that sin would be impossible. This impossibility of sinning only follows confirmation in goodness, and especially the beatific vision. The contrary excess would be a pessimism arising from dualism, which would lead to Manichaeism, that is, the doctrine of two principles. As Father Rousselot demonstrates in his thesis, “Pour l’histoire du problème de l’amour au Moyen Age,”4 there are various theories between these two mutually opposing excesses. There is already, therefore, in our nature an inclination to love God, the author of nature, more than ourselves. Conclusion 2. In the state of fallen nature, in order to love God, the author of nature, above all things efficaciously, man requires the help of grace restoring nature. (Cf. the end of the article’s conclusion.) The proof given in the words of St. Thomas is as follows: “because, on account of the corruption of nature, the will adheres to a private good, unless cured by the grace of God.” In other words, unless cured by grace, man does not refer to God, efficaciously loved as an end, his love of self and of all other things; thus, unless cured by grace, man does not love God more than himself with a natural love. And inasmuch as this disordered inclination is perverse, it is called an inordinate love of self, self-love, or egoism. By original sin, man’s will is directly averse to his final supernatural end and indirectly to his final natural end. For every sin against the supernatural law and end is indirectly against the natural law which prescribes that God is to be obeyed, whatever He commands. Hence fallen man is averse to God as his final end even naturally. Conclusion 3. Man in any state requires the help of special grace to love God, the author of grace, with an infused, supernatural love (cf. ad I). This is of faith, contrary to Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism (Council of Orange, can. 17, 25; Denz., nos. 190, 198; Council of Trent, Sess. VI, can. 3; Denz. no. 813). It was declared that “if anyone should say that, without a prevenient inspiration of the Holy Ghost and His assistance, man can believe, hope, love, or repent in such a way that the grace of justification would be conferred on him, let him be anathema.” This definition of faith is based on the texts of Sacred Scripture quoted at the Council of Orange as follows: “The charity of God is poured forth in our hearts, by the Holy Ghost, who is given to us (Rom. 5:5). “No man can say the Lord Jesus, but by the Holy Ghost” (I Cor. 12:3). “The fruit of the Spirit is charity, joy, peace” (Gal. 5:22). “Peace be to the brethren and charity with faith, from God the Father, and the Lord Jesus Christ” (Ephes. 6:23). “Dearly beloved, let us love one another, for charity is of God. And everyone that loveth, is born of God, and knoweth God. He that loveth not, knoweth not God: for God is charity” (I John 4:7 f.); that is, he does not know, as it were, experimentally, with an affective knowledge. Baius and Quesnel said that he does not know in any way. In regard to the explanation of this third conclusion, see the reply to the first objection, which was quoted against Baius. St. Thomas says: “Nature loves God above all things since God is the beginning and end of natural good; charity, however, loves God since He is the object of (supernatural) beatitude and since man has a certain spiritual fellowship (by grace) with God.” From which is to be intimated what man would be capable of even in the state of pure nature. Cf. IIa IIae, q. 26, a. 3, where it is declared that: “We can receive a two-fold good from God, the good of nature and the good of grace. Moreover, natural love is based upon the communication of natural goods made to us by God. . . . Hence this is much more truly evident in the friendship of charity, which is based upon the communication of the gifts of grace.” Again in the reply to the second objection: “Any part loves the good of the whole according as it is becoming to itself, not however in such a way as to refer the good of the whole to itself, but rather so as to refer itself to the good of the whole.” And in reply to the third objection: “We love God more with a love of friendship than with a love of concupiscence, for the good of God is in se greater than the good which we can share by enjoying Him.” And thus, absolutely, man loves God more in charity than himself. And he loves the God who is to be seen more than the beatific vision or the created joy following upon this vision. Thus, it may be said (IIa IIae, q. 17, a. 6 ad 3): “Charity (inasmuch as it surpasses hope) properly causes a tending toward God, uniting the affections of a man with God, so that man does not live for himself but for God.” This is pure love properly understood, that is, above hope; but not excluding hope, as the Quietists would have it. Doubt. Whether in the state of pure nature man would be able to love God the author of nature, above all things, with a natural love. Reply. Thomists generally reply in the affirmative. 1. On account of the universality of the principle invoked by St. Thomas (Ia, q. 60, a. 5, and in the present article): “Every creature according to its being as such, is of God, and therefore it loves God with a natural love more than self.” This principle is valid for any natural state in which there is no disorder. But in the state of pure nature there would be no disorder. 2. In Quodl., I, a.8, St. Thomas enunciates the principle of our article in a very comprehensive way, so that it would be valid for any natural state in which there is no perversion. 3. Since it is said (Ia, q. 60, a. 5) that, “if (man) were to love himself naturally more than God, it would follow that natural love would be perverse, and that it would not be perfected by charity but destroyed.” But this natural love would not be perverse in the state of pure nature. Therefore. 4. Since man in the state of pure nature would not be born, as now, habitually averse to his final supernatural end directly and to his final natural end, but the possibility of conversion or aversion. Corollary. Man has less powers in the state of fallen nature for naturally doing what is morally good than he would have in the state of pure nature. This is contested by several authors of the Society of Jesus. II.CONFIRMATION OF THIS DOCTRINE OF ST. THOMAS FROM THE CONDEMNATION OF BAIUS (cf. Denz., nos.1034, 1036, 1038) AND QUESNEL (Denz.,nos. 1394-95)5 The entire solution may be reduced to the following:

Hence it must be firmly maintained that the natural love of God above all things is the supreme precept of the natural law, and with still greater reason does this hold in the supernatural order, as it was already formulated in Deut. 6:5: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with thy whole heart”; but there it was proclaimed as a law of thesupernatural order as well, as also in Matt. 22:27, Mark 12:30, Luke 10:27. But the natural law is neither abolished by sin nor given by grace, since it is naturally stamped upon creatures. III. CONTROVERSIES AMONG MODERN THEOLOGIANS ON THIS SUBJECT The controversy is twofold, first on natural love and secondly on supernatural love. The first problem is whether fallen man can, without repairing grace, love God the author of nature above all things with a love that is affectively efficacious. (Cf. Billuart, De gratia, diss. III, a. 3.) The second problem is whether the act of the love of God, author of grace, considered substantially, is impossible without grace. Molina denies this. First of all the terminology must be explained as follows:

1. It is certainly true that without grace there can be: a) an innate love or natural inclination to love God above all things; this is the faculty of the will itself; b) a necessary, elicited love of God vaguely loved in happiness in general, which all desire; in this case God is not loved above all things, since He is not considered as distinct from all other goods; c) a free inefficacious love, or simple complacency in the goodness of God, not going so far as to adopt means of pleasing God nor of withdrawing from mortal sin, for which natural concurrence would be adequate. Thus many poets have written beautiful poems on the goodness and wisdom of God, ruler of the world, but without the intention of reforming their voluptuous lives. 2. We shall see in the following article that effectively efficacious love, at least absolutely, or the practice of all the commands of the natural law which are gravely obligatory, cannot now be possessed without a special healing grace. 3. The controversy, therefore, concerns affectively efficacious love, by which God, author of nature, distinctly known, is loved with esteem above all things, with the intention of pleasing Him in all things and of withdrawing from mortal sins against the natural law. Thomists maintain that this affectively efficacious love cannot exist in fallen man without healing grace.6 And in this regard they differ especially from Molina, who teaches that fallen man can, by his natural powers, thus love God, the author of nature, with an affectively efficacious love, and even, after having been instructed in the teaching of faith, can, likewise by his natural powers, love God as author of grace substantially, although not in respect to supernaturalness of mode, which is bestowed by charity. 7 Molina adds to this that the affectively efficacious natural love of God, author of nature, is not meritorious of grace (that would be Semi-Pelagianism) but, on account of the covenant between God and Christ the Redeemer, if man thus does what in him lies through his natural powers, God will not refuse sanctifying grace.8 With still greater reason, for Molina, if anyone imbued with the doctrine of faith undertakes an act, natural substantially, of affectively efficacious love of God, author of grace, God infuses charity, and this love become supernatural in respect to mode and thus available for salvation. Scotus, Gabriel, and certain others are cited as holding the same opinion. Against the first of these teachings of Molina on the possibility of an affectively efficacious love of God, author of nature, above all things without grace, Thomists declare that: 1. This doctrine does not seem to preserve sufficiently the sense of the words of the Council of Orange (can. 25; Denz., no. 199): “We must believe that by the sin of the first man free will was so inclined and weakened that no one subsequently is able either to love God as he ought, . . . or to do for the sake of God what is good, unless the grace of mercy anticipates him.” The Molinists reply that the Council says, “as he ought with regard to salvation,” and hence refers only to supernatural love. To this the Thomists answer that the Council is not referring to supernatural love alone, since it repeats that the impotence to love God above all things arises not from the supernaturalness of the act but from the infirmity of fallen nature; therefore it refers to natural love as well, since the impotence arising from the supernaturalness of the act was already present in the state of innocence. This also seems to be the meaning of the Council of Trent (Sess. VI, can. 3; Denz., no. 813): “If anyone should say that without the inspiration of the Holy Ghost and His assistance man can believe, hope, love, or repent as is required in order that the grace of justification should be granted to him, let him be anathema.” Nevertheless, the Thomists add, it is not possible for the grace of justification not to be conferred upon one who loves God, the author of nature, above all things with an affectively efficacious love. (Cf. below, q. 109, a. 6, on whether man, without grace, can prepare himself for grace, and q. 112, a. 3.). Moreover, the aforesaid teaching of Molina is contrary to the final proposition of the body of the present article of St. Thomas, where he contrasts the state of fallen nature with that of integral nature: “In the state of corrupt nature, man requires the help of grace healing nature, even for loving God naturally above all things.” There is no doubt but that St. Thomas is speaking also of affectively efficacious natural love, that is, with the intention of pleasing God in all things and of withdrawing from mortal sin. This is confirmed by what has been said above (Ia IIae, q. 89, a. 6): “When man begins to have the use of reason . . . (he should) deliberate concerning himself. And if anyone orders his life toward the proper end (that is, to God even as author of nature), he will obtain the remission of original sin by grace. In the present article St. Thomas is not yet speaking of effectively efficacious love, that is, of the fulfillment of every natural precept; but he refers to it in the following article. Finally, the opinion of Molina is thus refuted by theological argument: A weak power, inclined to selfish good opposed to the divine, cannot produce the superior act of a healthy power with reference to God, unless it is healed. But man in the state of fallen nature has a weak will, inclined to a selfish good. Therefore he cannot produce a preeminent work with reference to God. This act is pre-eminently that of a healthy power, since it virtually contains the fulfillment of the whole natural law, for the actual accomplishment of the law follows from the efficacious will to fulfill it. Hence grace is necessary not only for the actual observance of the whole natural law, but also for the intention of fulfilling it. Nor is the eflicacious natural volition granted for accomplishing anything which is now naturally impossible. This weakness of the will consists in its “following a selfish good unless healed by the grace of God,” as stated in the article. In other words, it is turned away from God and even its natural final end; for sin offends God even as author of nature. Moreover, it is a disorder of the concupiscence which the demon augments and enkindles. First doubt. What, then, of the natural love of God in the separated souls of children who die without baptism, of whom St. Thomas speaks (IIa, d. 33, q. 2, a. 2 ad 5)?Reply. There is, first of all, an innate love and a necessary, elicited mlove of God, confusedly, as in happiness in general, for this love remains even in the demons (Ia, q. 60, a. 5 ad 5). Secondly, there is a free, imperfect, inefficacious love, or love of complacency, toward God as principle of all natural good, but not really an efficacious love. Otherwise we should have to deny the last proposition in the body of the present article. In this connection it seems that, as stated in a.2 ad 3, “Nature is more corrupted in regard to the appetite for good than in regard to the knowledge of the truth.” For the mind of fallen man is able by its own powers to judge speculatively that God is the highest good, lovable and worthy of love above all things; but without healing grace, he is incapable of recognizing this with his practical judgment, impelling him to action. Hence the words of Medea spoken of by the poet: “I see what is better, and I approve it (speculatively), but I follow what is worse.” Man, then, is more deeply wounded in his will by which he sins than in his intellect. If, therefore, a child, reaching the full use of reason, loves God, the author of nature, above all things with an affectively efficacious love, this can only be by means of healing grace. Objection. Fallen man can, without grace, love his country, or his friend, or his chastity more than his own life; therefore, with still greater reason can he so love God, the author of nature. Reply. I reply by distinguishing the antecedent: fallen man does this without the special help of God, if it is done from a worldly motive, such as the desire for fame or glory, granted; but if from the pure motive of virtue, denied; for this requires the special help of God, as conceded to many pagans, according to Augustine. Moreover it is more difficult to love God, the author of nature, above all things in a manner that is affectively efficacious than to love the attractiveness of any particular virtue more than one’s life; for this is, at least virtually, to love all the virtues beyond all sensible feelings.This is more difficult; for instance that a soldier, ready to die for his country, is not willing to spare his enemy when he should. Second doubt. What grace is required for this affectively efficacious love of God, author of nature above all things? Reply. Of itself, by reason of its object, it requires only help of a natural order, but accidentally and indirectly, by reason of the elevation of the human race to the supernatural order, it requires supernatural help, that is, healing grace (as declared in the article). This is because the aversion to a final natural end cannot be cured without the aversion to a final supernatural end being cured; for this latter contains indirectly an aversion to the final natural end, for every sin against the supernatural law is indirectly against the natural law: God is to be obeyed, whatever He may command. Moreover, as we shall state in the following article, the love of God virtually includes the fulfillment of the whole natural law, for which supernatural healing grace is required. The Thomists also

reject the other opinion of Molina, that man imbued with the teaching of

faith can without grace love God, the author of grace, in respect to the

substance of this act, although not in respect to its mode as proper to

salvation. Contrary to this, the Thomists generally hold, as for the act

of faith, that the act is specified by its formal object; but the formal

object of the aforesaid act is God, the author of grace; therefore this

act is essentially supernatural, or supernatural in respect to substance

and not merely in respect to mode (cf. Salmanticenses, De Gratia,

disp. III, dub. III; and our De revelatione, I, 498, 511). A

natural act in respect to substance would be an act specified by a

natural object, such as an act of acquired temperance, which might yet

become supernatural in respect to mode, according as it is commanded by

charity and ordered by it to the reward of eternal life. ARTICLE IV.

WHETHER MAN, WITHOUT GRACE, BY HIS NATURAL POWERS,\ State of the question. In this article, as is evident in the body, we are especially concerned with the precepts of the decalogue which already belong to the natural law and can substantially be fulfilled without charity; indeed, even the acts of faith and hope can be accomplished in the state of mortal sin. Let us examine: 1. St. Thomas’ conclusions and arguments; 2. How they are based on Holy Scripture and tradition; 3. The refutation of the objections. (The article should be read.) I. ST. THOMAS’ CONCLUSION His first conclusion is that in the state of corrupt nature, man cannot, without healing grace, fulfill all the precepts of the natural law with respect to the substance of the works, while on the contrary he would be able to do this without grace in the state of integral nature (supposing, however, natural concurrence). From these last words, which are found in St. Thomas, it is evident that he is concerned in this instance with the precepts of the natural law in respect to the substance of the works, for the substance of a work correlative with a supernatural precept is supernatural and cannot, even in the state of integral nature, be produced without grace. In fact, precepts are called supernatural because they enjoin acts which surpass the powers of nature. In article two it is stated that “grace was necessary to man in the state of integral nature in order to perform or will a supernatural work.” The argument supporting this conclusion is the same as in the preceding article for the impossibility of loving God, author of nature, with an affectively efficacious love; indeed the argument now holds with still greater reason, that is, in the case of effectively efficacious love or the fulfillment of all the precepts of the natural law. In other words, a weak man cannot of himself perform the very superior work of a healthy man, unless he is first cured. Nor can a will turned away from even its natural final end be properly oriented in regard to all the means to that end. It would be rash to deny this first conclusion or to maintain that effectively efficacious love of God, author of nature, above all things can be attained without grace. This is conceded by the Molinists.9 It would be rash because the Council of Orange (Denz., nos. 181 ff., 199) refers not only to impotence arising from the supernaturalness of the work, but from the weakness of fallen nature. The second conclusion is that in no state can man without grace fulfill the commands of the law with respect to the mode of acting, that is, performing them from charity. This is of faith. St. Thomas makes the assertion without proof, for he has already said, in article two, that man even in the state of incorrupt nature required “grace added to nature in order to perform or will supernatural good,” and particularly to elicit a supernatural act of charity. For acts are specified by their objects and therefore the act specified by a supernatural object is essentially supernatural. II. THE BASES OF TRADITION They are as indicated by Billuart, in addition to many texts of St. Augustine. 1. The Council of Milevum (Denz., no. 105), against the Pelagians who declared that without grace man can keep all the commandments of God, but with difficulty; with grace, however, he can do so with facility; it is defined that “if anyone should say . . . that grace . . . is given to us that we may more easily fulfill the divine commands, and . . ., that, without it, we are able to fulfill them, although not easily, let him be anathema.” From this it is deduced that the commandments of God cannot be fulfilled as is necessary for salvation, that is, from charity, without grace. St. Augustine always defends this truth against the Pelagians in his De spiritu et littera, De gratia Christi, De libero arbitrio; in the book De haeresibus (heresy 88), speaking of the Pelagians, he says: “They are such enemies of the grace of God that they believe a man can accomplish all the divine commands without it.” Likewise, St. Augustine on Ps. 118, conc. 5, and in Sermon 148 (de tempore), chap. 5, where he is concerned with the precepts of the decalogue. The opposite error in Baius (Denz., nos. 1061,1062) was condemned because it rejects the distinction between fulfilling the commandments in respect to substance and in respect to mode, supernaturally. 2. The Council of Orange (II, c. 25; Denz., no. 199) declared: “We must believe that through the sin of the first man free will was so inclined and weakened, that no one has since . . . been able to perform what is good for the sake of God unless the grace of divine mercy precedes him.” Hence St. Thomas’ second conclusion is of faith; that is, without grace, men cannot fulfill the commandments with respect to supernaturalness of mode, namely, so as to be performed out of charity. And the Molinists admit this.Doubt. Whether grace is necessary for the fulfilling of any supernatural precept, in respect to its substance. Herein lies the controversy with the Molinists. Scotus and the Molinists hold that without grace men imbued with the teaching of faith can fulfill, substantially, even interior works correlative to the supernatural precepts of faith, hope, and charity. Reply. The Thomists reply that it is not possible, since precepts are called supernatural because they enjoin acts which, in themselves, essentially surpass the powers of nature, and these acts are such, in fact, because they are specified by a supernatural formal object. Thus, for example, an act of Christian faith differs from an act of acquired temperance. Insistance by Molina, Lugo, and Billot, that diversity of the activating principles (that is, of habits) alone is sufficient to cause acts to differ in species, even when they attain the same formal object. Reply 1. These very activating principles, that is, habits and powers, should be specified by the formal object. 2. The Salmanticenses reply (De gratia, disp. III, dub. III, no. 60): “I deny the antecedent, for if it were true, as our adversaries contend, nothing in true philosophy but would waver (or be overturned) in regard to species and the distinction of powers and habits; we should be compelled to establish new bases such as were not taught by Aristotle, Master Thomas, or the leaders of other schools. Although younger writers would easily grant this, we should have no leader from among the ancients. The result would indeed be to the highest detriment of true wisdom; wherefore it is essential in this respect to hinder their proclivity with all our powers.” Cf. other texts of the Salmanticenses quoted in our De revelatione, I, 495. To the same effect Thomas de Lemos, O.P., replied in the celebrated discussions of the Congregatio de Auxiliis, on May 7 and 28, 1604, before Clement VIII (cf. De revelatione, I, 491). He challenged the opinion of Molina in the following words: “By which system he would overturn faith as well as philosophy; faith, certainly, because thus God is feared and loved by the powers of nature, as the end is supernatural; philosophy indeed since, in this way, the formal object of a superior habit is attained by the inferior powers.” And on May 28, 1604, session 54 settled a problem proposed according to the interpretation of the Thomists explained by Lemos. Lemos expresses the same opinion in his Panoplia gratiae at the beginning of Bk. IV, nos. 24f. (Cf. De revelatione, I, 491; Del Prado, De gratia, I, 48; Suarez expresses agreement with us in De gratia, Bk. II, c. II, nos. 22 f., quoted in De revelatione, ibid.) Thus Suarez, as well as Lemos and the Salmanticenses considers it rash to deny the aforesaid traditional teaching of theologians. In respect to this matter many Jesuits follow Suarez, including the Wirzburg school (De virtutibus theologicis, disp. II, c. III, a. 3); Bellarmine is also cited and, among more recent writers, Wilmers (De fide divina, 1902, pp. 352, 358, 375); Mazzella, in the first two editions of De virtutibus infusis, and Pesch (De gratia, nos. 69, 71, 410). Objection. The Molinists object, referring to Ia IIae, q. 54, a. 2 where it is stated that “the species of habits are distinguished in three ways: 1. according to the activating principles of such dispositions, 2. according to nature, 3. according to objects.” Therefore, declare the Molinists, habits are not specified only by their objects. Reply. All of these are to be taken together and not separately. An act cannot be essentially supernatural from the standpoint of its eliciting principle and according as it presupposes habitual grace unless it is at the same time supernatural from the standpoint of its object. Moreover, we contend in De revelatione, I, 506, in agreement with the Salmanticenses and other Thomists, that from St. Thomas’context it is clearly evident that, when he says habits are specified according to their active principles, he means according to their objective, regulating, specifying principles; for he says in the answer to the second objection of the same article: “The various means (of knowledge) are like various active principles according to which the habits of science are differentiated.” And in answer to the third objection: “Diversity of ends differentiates virtues as diversity of active principles” or motives according as the end is the object of a prior act of the will, in other words, the intention. Similarly in Ia IIae, q. 51, a. 3, St. Thomas shows that the regulating reason is the active principle of the moral virtues, and the understanding of principles is the principle of knowledge, that is, as proposing the formal object (objectum formale quo) or motive. Moreover, when he says that habits are specified according to nature, this is according as the habit is good or bad, suitable or not suitable to the nature; or according as it is suitable to human nature as such, or suitable to the divine nature in which man participates; but it cannot be of itself suitable to a higher nature, unless at the same time it has a formal object proportionate or of the same order; otherwise it would be an accidentally infused habit, such as infused geometry. Father Ledochowski, General of the Society of Jesus, further acknowledges that the teaching of Molina we are discussing is not that of St. Thomas (cf. De revelatione, I, 489). III. REFUTATION OF THE PRINCIPAL OBJECTIONS AGAINST THE NECESSITY OF GRACE FOR OBSERVING SUBSTANTIALLY ALL THE PRECEPTS OF THE NATURAL LAW The first classical difficulty is indicated by St. Thomas in the first objection, taken from the text of St. Paul to the Romans (2:14): “The Gentiles who have not the (written) law, do by nature those things which are of the law.” Reply. According to St. Augustine, followed by St. Prosper, St. Fulgentius, and by St. Thomas here in his refutation, these words are to be understood of the Gentiles acting from grace; and then “by nature” is not interpreted according as it is opposed to grace, and according as it is equivalent to “the powers of nature,” but according as it is opposed to the Mosaic law, so that the meaning is: “The Gentiles who have not the written law, do naturally those things which are of the law,” in other words, without the law of Moses, but not without the spirit of grace. Thus Augustine in De spiritu et littera, Bk. I, c. 27, quoted here by St. Thomas; likewise St. Chrysostom.”10 But other interpreters understand this of the infidel Gentiles and hence “by nature” of the powers of nature; but this disposes of the objection just as well, for the meaning is that the Gentiles by their own natural powers perform certain works of the law, but not all. The second difficulty is as follows: if the observance of the whole natural law, in respect to the substance of the works, is impossible to fallen nature, then the Jansenist heresy follows logically, that is, that certain of the precepts of God are impossible to fallen man. Luther and Calvin held the same opinion. Reply. “What we can do with divine assistance is not altogether impossible for us”; and we avoid Jansenism by declaring that the grace necessary to accomplish the commandments is not wanting to anyone except by reason of his own fault. All adults receive graces at least remotely sufficient for salvation, and if they did not resist them, they would obtain further graces. The error of Luther and Calvin is apparent from this: according to them, Christ did not come to form observers of the law, but to redeem the faithful from the obligation of observing the law, in accordance with Luther’s words : “Sin strongly and believe more strongly,” in other words, believe firmly that you are freely elect, and you are saved, even if you persevere in crimes and the transgression of the law until death. The Jansenists erred similarly by maintaining that certain commands of God are impossible not only to fallen man, but even to the just man. This is manifest from the first proposition of Jansen (Denz., no. 1092): “Other precepts of God are impossible to just, willing, zealous men with the powers which they now possess; they also lack the grace which would make them possible”; in 1653 this was condemned as heretical. The Council of Trent had previously defined (Denz., no. 804): “God does not command the impossible, but by commanding He urges you both to do what you can and to ask what you cannot, and He assists you that you may be able.” Also in the corresponding canon (Denz., no. 828). The foregoing words of the Council are taken from St. Augustine, and, according to them, sufficient grace to pray is never wanting, and by it man has at least the remote power of observing the divine precepts, for “by commanding, God urges you to do what you can and to ask what you cannot, and He assists you that you may be able.” I insist. God cannot demand that a blind man see, although he may see by a miracle; therefore, neither can He demand that fallen man observe the law, although he may do so by means of grace. Reply. The disparity lies particularly in the fact that the blind man is not offered a miracle which would cure him; but fallen man is offered grace by which he may observe the law, and he would receive it if he did not voluntarily set obstacles in the way. Hence one must pray as did Augustine, saying: “Lord, grant what Thou commandest and command what Thou wilt,” that is, give us grace to fulfill Thy commands and command what Thou wilt. First doubt. Which grace is required by fallen man for the keeping of the whole natural law?Reply. As in the explanation of the preceding article: of itself, by reason of its object, help of the natural order would suffice, since the object is natural. Accidentally, however, and by reason of the elevation of the human race to a supernatural end, supernatural grace is required, which under this aspect is called healing grace. This is because in the present economy of salvation man cannot be converted to God, his final natural end, and remain estranged from God, his supernactural end, since this aversion is indirectly opposed to the natural law, according to which we ought to obey God, whatever He may command. Second doubt. To observe the whole natural law for a long time is supernatural actual grace sufficient, or is habitual grace required? Reply. According to ordinary providence, habitual grace is required, by which alone man is solidly well disposed toward his final end. And this firm disposition toward his final end is itself required that man may keep the whole natural law enduringly and perseveringly. Nevertheless, by an extraordinary providence, God can fortify a man’s will in regard to the observance of all the natural precepts by means of continuous actual graces; but if a man does what lies within his power by the help of actual grace, God will not withhold habitual grace from him. As we shall see below (a. 9), over and above habitual grace, actual grace is required for the just man to perform any supernatural good work, and even to persevere for long in the observance of the whole natural law, in spite of the rebellion of the sense appetites against reason, and the temptations of the world and the devil. Third doubt. Whether in the state of pure nature man would be able to observe enduringly the whole natural law without special help of the natural order. Reply. I reply in the negative with Billuart: Since to do so demands constancy of the will in good against the ternmations that arise. A constancy which man established in the state of pure nature would not have had, of himself, with the aid of ordinary concurrence alone; hence, to persevere he would have had need of special natural help which God would have given to many, but not to those in whom He would have permitted the sin of impenitence of this natural order in punishment for preceding sins.Cajetan’s opinion. In his commentary on the present article, which preceded the disputes aroused by Molina, at a time when the terminology of this subject was not yet fully established, Cajetan spoke less accurately in explaining the answer to the third objection. He says, “man, by nature, can believe, hope, love God, with respect to the substance of the act,” and he cites the example of a formal heretic who adheres to certain dogmas. He expresses himself similarly in regard to IIa IIae, q. 171, a. 2 ad 3. But it is evident from the context and from this example that Cajetan is referring to the generic substance of the acts, not to the specific substance, not to the formal object itself (objectum formale quod et quo); for a heretic believes formally, not by divine, but by human faith.Later Cajetan

corrects his terminology (commenting on IIa IIae, q. 6, a. I, no. 3 ),

declaring that “it should be said, therefore, that the act of faith

springs forth as a result of no natural knowledge, of no natural

appetite, but from the appetite for eternal beatitude and from an

adherence to God supernaturally revealing and preserving His Church.”

Cajetan likewise defends the common opinion of Thomists against Scotus

and Durandus (Ia IIae, q. 51, a. 4): “Infused habits are of themselves

essentially supernatural.” Also, q. 62, a:3; q. 63, a. 6, and IIa IIae,

q. 17, a. 5, no. I, where he defends the opinion that with out infused

virtue there would be no act “proportionate to the supernatural object,”

nor to the supernatural end. (Cf. Del Prado, De gratia, I,

50 and our De revelatione, I, 484 f., note I.) ARTICLE V.

WHETHER MAN CAN MERIT ETERNAL After considering the observance of the divine commands in themselves, St. Thomas considers it in relation to eternal life. The question is here posed generally and indefinitely; later, in q. I 14, a. 1 2,3, here he is dealing with merit properly speaking, the question will be more particularly treated as to whether man without grace can merit de condigno eternal life. The answer is negative and is of faith, against the Pelagians. 1. It is proved from authority in the argument Sed contra (Rom. 6:23): “the grace of God life eternal,” which is thus explained by Augustine, here quoted: “that it may be understood that God, in His compassion, leads us unto eternal life.” St. Augustine is also quoted in the answer to the second objection. (Cf. Council of Orange, II, can. 7, Denz., no. 180; and Trent, Sess. VI, can. 2, Denz., no. 812.) 2. It is thus proved by theological reasons: Acts leading to an end must be proportionate to the end. But eternal life is an end exceeding the proportion of human nature (cf. Ia IIae, q. 5, a. 5, on supernatural beatitude). Therefore man cannot by his natural powers produce works meritorious of eternal life. Read the answer to the third objection with respect to the distinction between final natural end and supernatural end (cf. Contra Gentes, Bk. III, chap. 147, and De veritate, q. 14, a. 2). These references are clear, and whatever is to be said on this subject is reserved for consideration in q. 114, a. 1 and 2, that is, whether man can merit anything de condigno, and so merit eternal life. ARTICLE VI.