|

QUESTION 111

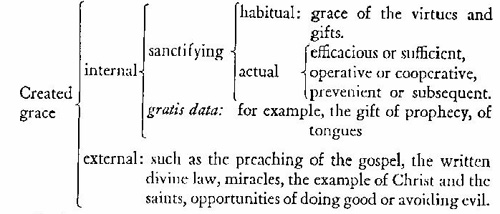

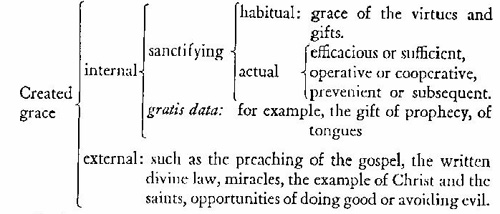

Having arrived at a definition of

sanctifying grace, we must now consider the divisions of grace. As a

matter of fact, at the beginning of this treatise, when we were

establishing our terminology, we enumerated the various significations

of created grace which may be reduced to the following outline.

In the present

question St. Thomas examines the basis of these principal traditional

divisions. He does so in five articles. The first and the last two deal

with the graces gratis datae as compared with sanctifying grace;

the second and third are concerned with the division into operative and

cooperative grace, prevenient and subsequent grace, this latter division

being the occasion for a discussion of efficacious and sufficient grace.

ARTICLE I.

WHETHER GRACE IS PROPERLY DIVIDED INTO

SANCTIFYING GRACE AND GRACE

GRATIS DATA

State of the question.

This article endeavors to explain the text of I Cor. 12:8-10, wherein

St. Paul enumerates nine graces gratis datae:

“To one indeed,

by the Spirit, is given the word of wisdom: and to another, the word of

knowledge, according to the same Spirit; to another faith in the same

spirit; to another the grace of healing in one Spirit: to another the

working of miracles; to another prophecy; to another the discerning of

spirits; to another diverse kinds of tongues; to another interpretation

of speeches”; and further (ibid., 12:31 and 13:1 f.): “I show

unto you yet a more excellent way. If I speak with the tongues of men

and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass or a

tinkling cymbal. And if I should have prophecy and should know all

mysteries and all knowledge, and if I should have all faith so that I

could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing.” (Cf. St.

Thomas on this Epistle.) From this contrast has arisen the traditional

division between the graces gratis datae, also called

charismata, and sanctifying grace. The statement of the question

will be more manifest from the problems raised at the beginning of the

article.

Reply.

St. Thomas shows the appropriateness of this traditional twofold

division.

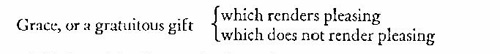

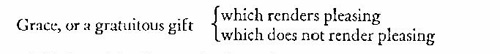

1. In the

argument Sed contra, on the authority of St. Paul who attributes

both characteristics to grace, namely, that of making us pleasing (“He

hath graced us,” Ephes. 1:6) and that of being a gratuitous gift (Rom.

11:6). Hence grace may be differentiated according to whether it

possesses but one of these notes, that is, being a free gift (and every

grace is gratuitous) or both notes, not only that of being given freely,

but also that of making us pleasing.

This is explained

more clearly in the answer to the third objection: “Sanctifying grace

adds something beyond the reason of graces gratis datae, . . .

that is, it makes man pleasing to God. And therefore grace gratis

data, which does not have this effect, retains merely the generic

name,” just as brute beasts are called “animals”; the name of the genus

is applied to the least distinguished member. Hence this division is

between an affirmation and a negation. In other words, grace in general

is defined as a supernatural gratuitous gift bestowed by God upon a

rational creature; and grace thus defined is divided according to

whether it renders him pleasing or does not. Thus grace gratis data

is not opposed, strictly speaking, to the other, in the sense that it

cannot be the object of merit, for neither can the first sanctifying

grace be merited, nor the last, that is, final perseverance, nor

eficacious actual grace to persevere in good acts throughout the course

of life. Nevertheless, as stated in the body of the article, grace

gratis data is granted over and above the merits of the person. (Cf.

below, q. I 14.)

2. By a

theological argument the appropriateness of the aforesaid divisions is

proved from a consideration of the ends.

Since grace is

ordained to the end that man may be restored to God, grace is twofold

according to the twofold restoration to God.

But the

restoration to God is twofold, thus: 1. uniting man himself to God

immediately, and this is effected by sanctifying grace; 2. not of itself

uniting man to God, but causing him to cooperate in the salvation of

others, and this is brought about by grace gratis data.

Therefore this

traditional division is correct. In other words, the union with God is

either formal or only ministerial. This division is adequate since to

render pleasing and not to render pleasing are contradictory opposites

to one another and there can be no middle ground between them. Grace

gratis data is per se primarily ordained to the salvation of

others, or “unto profit.”1

Sanctifying grace is per se primarily ordained to the salvation

of the recipient, whom it justifies.

It should be

noted that these two statements are qualified as “per se

primarily,” that is, essentially and immediately; however, grace gratis

data may secondarily lead to the salvation of the recipient, provided,

that is, it be employed by charity. Likewise, sanctifying grace may

secondarily lead to the salvation of others through the example of

virtue. But the primary end of each is the one assigned to it above.

Corollary.

Unlike sanctifying grace, the graces gratis datae may sometimes

be found in the wicked or sinners; for although sinners neglect their

own salvation, they may procure the salvation of others and cooperate in

it, after the manner of those who built Noah‘s ark and yet were

submerged in the waters of the flood.

Thus Caiphas

prophesied as one divinely inspired, saying “It is expedient . . . that

one man die for the people” (John 11:50). Again, as narrated in the Book

of Numbers (23:22 ff.), Balaam, although a soothsayer and idolater,

received the gift of prophecy; likewise the sibyl, in spite of being a

pagan. (Cf. IIa IIae, q. 172, a. 4); with respect to prophecy (q.178, a.

2), the wicked can perform miracles in order to confirm revealed truths;

but if the gift of prophecy, which is the highest among the graces

gratis datae, exists in the wicked, with still greater reason is

this true of the others. Hence St. Paul himself says: “I chastise my

body, . . . lest perhaps, when I have preached to others, I myself

should become a castaway” (I Cor. 9:27).

Doubt.

Whether “sanctifying grace” can be taken in a twofold sense.

Reply.

Undoubtedly. 1. Strictly, it refers to habitual grace, distinct from the

infused virtues, by which we are justified or formally rendered pleasing

to God. 2. Broadly, it includes that which is ordained to the

justification of its subject, whether antecedently as stimulating grace

which disposes us for justification, or concomitantly, or consequently,

as, for example, supernatural helps, the infused virtues, the gifts, the

increase of grace, and glory, which is the consummation of grace. In the

present question sanctifying grace is thus broadly taken in contrast to

grace gratis data. And thus the aforesaid division is adequate.

Vasquez did not take this extended use of the term into account when, in

commenting on the article, he declared this division to be insufficient

since faith, hope, and actual helps could not be found under either of

its members. Hence sanctifying grace is identical here with the “grace

of the virtues and gifts with their proportionate helps,” which St.

Thomas speaks of (IIIa, q. 62, a. I): whether sacramental grace adds

something over and above the grace of the virtues and gifts. Indeed to

sanctifying grace also belong the sacramental graces which are the

proper effects of the sacraments; for example, baptismal grace, the

grace of absolution, of confirmation, nutritive grace (cf.p. 148 above).

Corollary. It is of great importance to determine clearly whether

infused or mystical contemplation, according as it is distinguished from

private revelations, visions, and even from words of wisdom or

knowledge, pertains to sanctifying grace and is in the normal way to

sanctity, or to the graces gratis datae as something

extraordinary. Theologians generally teach that infused contemplation

belongs to sanctifying grace, or to the grace of the virtues and gifts;

it is something not properly extraordinary but eminent, for its proceeds

not from prophecy but from the gifts of wisdom and understanding as they

exist in the perfect. Cf. IIa IIae, q. 180, on contemplative life, after

he considered graces gratis datae in particular.

Let us pass immediately to articles four and five which deal with the

same material, because afterwards there will be a longer consideration

of articles 2 and 3 with reference to operative and cooperative grace,

sufficient and efficacious grace.

ARTICLE IV.

WHETHER GRACE GRATIS DATA IS ADEQUATELY SUBDIVIDED BY THE

APOSTLE (I COR. 12:8-10)

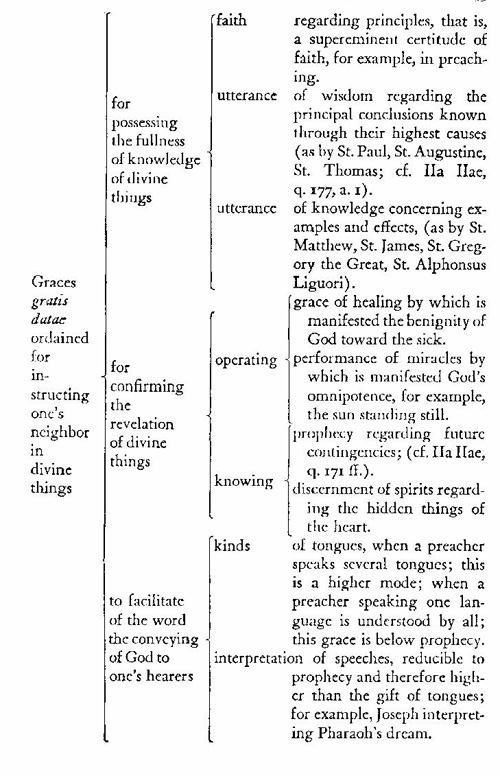

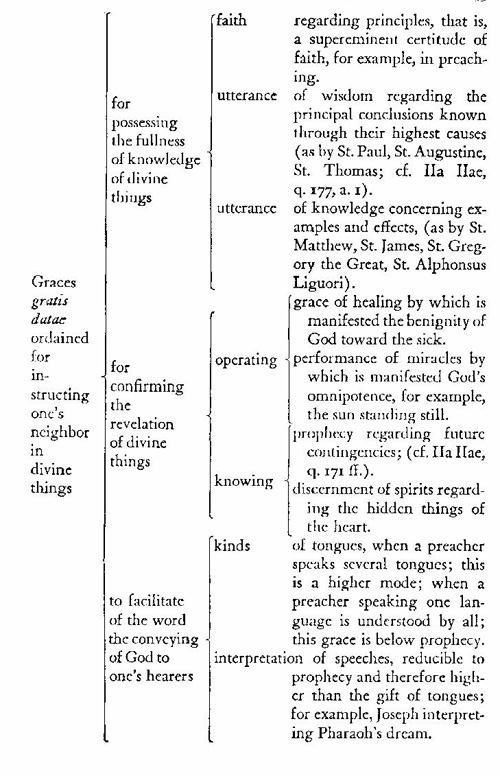

State of the question. St. Paul here enumerates nine graces

gratis datae. St. Thomas shows the appropriateness of this division.

Many Thomists, Gonet among them, hold this division to be adequate; so

also does Mazella. On the other hand, Medina, Vasquez, Bellarmine,

Suarez, and Ripalda do not consider this division all-embracing, but

maintain that St. Paul was enumerating only the principal graces.

Suarez would further add to them the priestly character, jurisdiction in

the internal forum, and the special assistance conferred upon the

Sovereign Pontiff.

St. Thomas seems to judge the enumeration given by St. Paul to be

entirely sufficient and he defends it brilliantly in a remarkable

discussion both here and in his commentary on I Cor. 12 (cf. De

revelatione, I, 209).

It should be noted that St. Thomas, treating of these graces in

particular (IIa IIae, q. 171-79) in that case divides them according as

they pertain either to knowledge or to speech or to action; and under

the heading “prophecy” he includes all those which refer to the

knowledge of divine things, except words of wisdom and knowledge. For

those which pertain to prophecy are knowable only by divine revelation,

whereas whatever is included under words of wisdom and science and

interpretation of speeches can be known by man through his natural

reason, although they are manifested in a higher mode by the

illumination of divine light.

Confirmation from the refutation of objections.

1. The graces gratis datae exceed the power of nature, as when a

fisherman is fluent in words of wisdom and science; they are thus

differentiated from the natural gifts of God which likewise do not make

us pleasing to God.

2. The faith of which it is a question here is not

the theological virtue present in all the faithful, but a supereminent

certitude of faith by which a man is rendered capable of instructing

others in the things that pertain to faith.

3. The

grace of healing, the gift of tongues, and the interpretation of

speeches possess a certain special motivation impelling faith, according

as they excite admiration or gratitude. In the grace of healing the

benignity of God toward the misery of man shines forth; in the

performance of miracles, such as the opening of a passage through the

sea or the stopping of the sun in its course, the omnipotence of God

appears.

4. Wisdom

and knowledge are included among the graces gratis datae not

because they are gifts of the Holy Ghost, but because, by means of them,

a man may instruct others and vanquish his opponents. Therefore they are

purposely set down in the present enumeration as utterances of wisdom or

knowledge. (Cf. St. Thomas, IIa IIae, q. 45, a. 5 and on I Cor. 12, lect.

2.)

According to Thomists, in opposition to Suarez, the sacramental

character and jurisdiction in the internal forum, and the assistance of

the Holy Ghost do not belong to the graces gratis datae, but to

the ministries and operations which St. Paul himself distinguishes from

the graces gratis datae.“There are diversities of graces, but the

same Spirit; and there are diversities of ministries, but the same Lord;

and there are diversities of operations, but the same God.” And they are

indeed distinguished, as Billuart observes, inasmuch as grace gratis

data concerns only an act which manifests faith, whereas

ministration or the ministry refers to the authority to perform some act

with respect to other men, such as the apostolate, the episcopate, the

priesthood, or any other dignity. An operation, moreover, is the

exercise of a ministry. Thus in the Old Testament priests and prophets

were differentiated.

Doubt. Whether the aforesaid graces gratis datae reside in

man after the manner of a habit or rather as a transient movement. (Cf.

Gonet, De essentia gratiae.)

Reply. Gonet replies: Generally they are present as transient

movements, such as the gift of prophecy, the grace of healing or of

prodigies, the discerning of spirits. This is evident from the fact that

a prophet or wonderworker does not prophesy or work miracles whenever he

wills. (Cf. IIa IIae, q. 171, a. 2.)

However, according to the same authority, faith, words of wisdom and of

knowledge do exist after the manner of habits, since one who receives

them uses them when he so wills.

In Christ all these graces were present as habits for two reasons.

1. On account of the hypostatic union He was an instrument united to the

divinity.

2. He had supreme power, by reason of which He disposed of all creatures

and hence at will He could perform miracles or cast out demons, as

explained in the treatise on the Incarnation, IIIa, q. 7, a. 7 ad I.

ARTICLE V.

WHETHER GRACE GRATIS DATA IS SUPERIOR TO SANCTIFYING GRACE

This question is of great importance with respect to mystical theology;

for example, which are higher among the works of St. Theresa, those

which pertain to sanctifying grace or those pertaining to graces

gratis datae?

State of the question. It seems that grace gratis data is

superior: 1. because the good of the Church in general, to which graces

gratis datae are ordained, is higher than the good of one man, to

which sanctifying grace is ordered; 2. because that which is capable of

enlightening others is of greater value than that which only perfects

oneself; it is better to enlighten than merely to shine; and 3. because

the graces gratis datae are not given to all Christians, but to

the more worthy members of the Church, especially to the saints.

However, in spite of these arguments, St. Thomas’ conclusion is in the

negative; and so is that of theologians generally.

The reply is: Sanctifying grace is much more excellent than grace

gratis data.

First proof, from the authority of St. Paul, who, after

enumerating the graces gratis datae, continues: “And I show unto

you yet a more excellent way. If I speak with the tongues of men and of

angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass or a

tinkling cymbal. And if I should have prophecy and should know all

mysteries and all knowledge, and if I should have all faith so that I

could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing’’ (I Cor.

12:31-13:2). But prophecy is the highest of all the graces gratis

datae (cf. IIa IIae, q.171), and this is said to be below charity,

which pertains to sanctifying grace. Therefore.

In his commentary on the first Epistle to the Corinthians (chap. 13),

St. Thomas thus explains the words “I am nothing,” that is, with respect

to the being of grace, described in Ephesians (2:10): “For we are His

workmanship, created in Christ Jesus in good works”; likewise II Cor.

5:17, and Gal. 6:15.

In the same place it is shown that charity surpasses all

these charismata in three respects:

1. From necessity, since without charity, the other gratuitous gifts do

not suffice.

2. From utility, since it is through charity that every evil is avoided

and every good work performed. “Charity is patient, . . . beareth all

things, hopeth all things, endureth all things.”

3. From its permanence, for “charity never falleth away,” as St. Paul

declares, whether prophecies shall be made void or tongues shall cease.

Hence charity is said to be the bond of perfection uniting the soul to

God and gathering together all other virtues to ordain them toward God.

Therefore can Augustine say: “Love and do what you will.”

Second proof from theological argument.

The excellence of any virtue is higher according as it is ordained to a

higher end; and the end is superior to the means.

But sanctifying grace ordains men immediately to union with his final

end; and the graces gratis datae ordain him toward something

preparatory to his final end, since by miracles and prophecies men are

led to conversion.

Therefore sanctifying grace is much more excellent than grace gratis

data.

In a word, sanctifying grace unites man immediately to God, who dwells

in him; on the other hand, grace gratis data serves only to

dispose others for union with God. This argument appears even more

profound when we observe that sanctifying grace, inasmuch as it unites

man immediately to God, his final supernatural end, is supernatural

substantially. It is indeed the root of the theological virtues which

are immediately specified by their formal supernatural object (objectum

formale quo et quod), and it is the seed of glory, the beginning of

eternal life which is essentially supernatural.

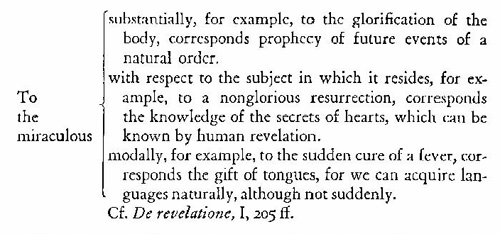

On the contrary, the graces gratis datae are generally

supernatural. only with respect to the mode of their production, in the

same way as miracles. As a matter of fact, with respect to this

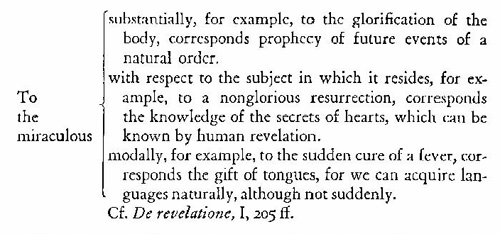

supernaturalness, the division of the charismata corresponds to

the division of miracles given by St. Thomas (Ia, q. 105, a. 8); the

comparison may be made as follows:

Thus the great

difference becomes evident between the supernatural substantially and

the miraculous substantially; in the former “substantially” means

formally, by virtue of its formal object; in the latter “substantially”

means effectively, or concerning an effect the substance of which cannot

be produced by a created cause in any manner or in any subject, such,

for instance, as the glorification of the body.

Hence below intrinsically supernatural knowledge, such as the beatific

vision or infused faith, there exist the following three kinds of

effectively supernatural knowledge the object of which is intrinsically

natural.

1.

Effectively, with respect to the substance of cognition, such as the

prophetic knowledge of future natural events taking place at a remote

time. This exceeds every created intellect, not by reason of the

essential supernaturalness of its object, as would be that of the

Trinity, but by reason of the uncertainty or indetermination of the

future, for example, the date when some war would end.

2. Effectively,

with respect to the subject in which it resides, such as the knowledge

of a natural object already actually existing, but removed in regard to

place or exceeding the faculty of vision of this particular man,

although not of all men (IIa IIae, q. 171, a. 3). Likewise the knowledge

of the secrets of hearts which are known nat-urally by the person whose

secrets they are.

3. Effectively, modally, such as the instantaneous knowledge of some

human science or unknown tongue without human study. Thus the

supernaturalness of prophecy is of an inferior order to the

supernaturalness of divine faith. Therefore St. Thomas says (III Sent.,

d. 24, a. 1 ad 3): “Although prophecy and faith treat of the same

matter, such as the passion of Christ, they do not do so in the same

way; for faith considers the Passion formally under the aspect of

something which borders on the eternal, that is, according as it was God

who suffered, although materially it considers a temporal event. This is

not true of prophecy.”

But what has been said of the supernaturalness of prophecy, the highest

of all the graces gratis datae, can be said of all the

charismata, as is very evident in the case of the gift of tongues,

the grace of healing, the performing of prodigies, and the discernment

of spirits. The same may be said of utterances of wisdom and knowledge

and of the interpretation of speech, for these latter three supply in a

supernatural way for what would be attained naturally by acquired

theology or hermeneutics. Thus, in general, the charismata are

supernatural modally only, and therefore sanctifying grace, which is

supernatural substantially, as a participation in the divine nature, is

“much more excellent,’’ as St. Thomas declares.

Confirmation of the aforesaid conclusion from the refutation of

objections.

First objection. The common good of the Church is better than the

good of one man. But sanctifying grace is ordained only to the good of

one, whereas grace gratis data is ordered to the common good of

the Church. Therefore.

Reply. The major is to be distinguished: the common good which is

in the Church is below the separated common good, that is, God: granted;

otherwise, denied.

I distinguish the minor: sanctifying grace is ordained to the good of

the individual and also to the separate common good, that is, to God to

whom it unites us immediately: granted; otherwise, denied.

Hence, above the common good of the Church, which is the ecclesiastical

order, there is the separate common good, which is God Himself, to whom

sanctifying grace unites us immediately. Similarly, above the common

good of an army, which is its order, there is the common good considered

separately, namely, the good of the country.

On this account St. Thomas says later (IIa IIae, q. 182, a. 1-4) that

contemplative life, which is immediately ordained to the love and praise

of God, is, in an absolute sense, better, higher, and more meritorious

than the active life, which is ordained toward the love of neighbor and

to the common good of the Church not considered apart. Therefore did

Christ say (Luke 10:42): “Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall

not be taken away from her.” Many moderns would do well to read this

response to the first objection.

Again St. Thomas declares (IIa IIae, q. 182, a. I ad I): “It not only

pertains to prelates to lead the active life, but they should also excel

in the contemplative life”; which St. Gregory had already expressed in

the words: “Let the leader be eminent in action, and sustained in

contemplation above all others.”

Second objection. It is better to enlighten others than merely to

be enlightened; but by the graces gratis datae man enlightens

others; by sanctifying grace he is only enlightened himself. Therefore.

Reply. I distinguish the major: it is better than merely to be

enlightened to enlighten others formally: granted; to enlighten others

merely by disposing them: denied.

I distinguish the minor: that man, by grace gratis data,

enlightens others formally: denied; by disposing them, granted; on the

contrary he is formally enlightened by sanctifying grace.

For, by the graces gratis datae man cannot produce sanctifying

grace in another, but only offer him certain disposing or preparatory

factors toward justification, such as preaching to him or performing

miracles. God alone directly or through His sacraments infuses

sanctifying grace. Similarly, in the natural order, St. Thomas

maintains, the heat by which fire acts is not more estimable than the

form of fire itself.

I insist. Then St. Thomas was wrong when he said later (IIa IIae,

q. 188, a. 6) that the apostolic or mixed life “proceeding from the

fullness of contemplation is to be preferred absolutely to

contemplation, since it is a greater thing to enlighten than merely to

shine.”

Reply. The apostolic life is preferred to simple contemplation

inasmuch as it includes this and something more; on the contrary, grace

gratis data does not include sanctifying grace and something

more.

Third objection. That which is proper to the more perfect is

better than that which is common to all. But the graces gratis datae

are gifts proper to the more perfect members of the Church. Therefore

they are higher than the grace common to all the just, as reasoning

power is superior to sensation.

Reply. There is a disparity, for sensation (which is common to

all animals) is ordained to ratiocination. But on the contrary the

graces gratis datae (which are proper) are ordained to the

conversion of men, in other words, to sanctifying or justifying grace.

First corollary. Sanctifying grace or the grace of the virtues

and gifts belongs to the normal supernatural. But it exists in three

degrees, that of beginners, proficients, and perfect; in other words,

the purgative, illuminative, and unitive ways, the last being the age of

maturity of the spiritual life.

Second corollary. The graces gratis datae belong to the

extraordinary supernatural, so called not so much in relation to the

Church as to the individual, for example, private revelations, visions,

and internal words pertaining to prophecy.

Third corollary. Infused contemplation, proceeding from the gifts

of wisdom and understanding as they exist in the perfect, is therefore

not something extraordinary, like prophetic revelation, but something

normal and eminent, that is, in the normal way of sanctification.

Fourth corollary. Cajetan In llam llae, q. 178, a.2 (quoted by

Father Del Prado, De gratia et libero arbitrio, p. 268): “It is a

most pernicious error to consider the gift of God in the working of

miracles to be greater than in the works of justice. And this, contrary

to the popular idea and common error of humankind, which judges men who

perform miracles to be saints and, as it were, gods, whereas these

dullminded people have almost no esteem whatever for just men. The

complete opposite ought to be considered of high value, as it truly is.”

Although the sanctity of the servants of God is outwardly manifested by

miracles, the saint who performs more miracles than another is not, on

that account, a greater saint.

Fifth corollary. Del Prado (op. cit., p. 261): “The

graces gratis datae may exist without sanctifying grace for the

manifesting of divine truth; for of themselves they do not justify.

Hence St. Thomas says, commenting on I Cor. (13, lect. 1): ‘It is

obvious with regard to prophecy and faith, that they may be possessed

without charity. But it is to be remarked here that firm faith, even

without charity, produces miracles. Wherefore the apostle Matthew

(7:22), in reply to those who will ask: ‘Have we not prophesied in Thy

name . . . and done many miracles?’ declares that our Lord will reply:

‘I never knew you.’ For the Holy Ghost works prodigies even by the

wicked, just as He speaks truth through them.”

Sixth corollary. However, the graces gratis datae are, in

the saints, also a manifestation of their sanctity (Del Prado, ibid.);

cf. St. Thomas on I Cor. (12, lect. 2); whence it is said in Acts (6:8)

that “Stephen, full of grace and fortitude, did great wonders and signs

among the people.”

ARTICLE II.

WHETHER GRACE IS

PROPERLY DIVIDED

INTO OPERATIVE AND COOPERATIVE GRACE

State of the question. This article

explains the division made by St. Augustine (De gratia et libero

arbitrio, chap. 17); it should be carefully studied, for Molina

maintains (Concordia, q. 14, a. 13, disp. 42, p. 242) that St.

Thomas misinterprets Augustine. After giving his own interpretation,

Molina says: “This is manifest in the clearest light, although Augustine

has been understood otherwise by St. Thomas (Ia IIae, q. III, a. 2 and

3), by Soto and by certain others.” In fact, Molina attempts to

demonstrate (ibid., p. 243) that Augustine cannot be interpreted

in any other way, in the light of faith. Since this is a most serious

charge, the question must be considered attentively.

The principal

point at issue between Thomists and Molinists on this subject may be

formulated thus: For Molina (Concordia, p. 565), Suarez

and their disciples, operative

actual grace urges only by moral, and not by physical, impulsion, and

leads only to indeliberate acts, but never of itself alone to free

choice or consent. But cooperative actual grace, according to Molina,

produces, by moral impulsion, a free choice, with simultaneous

concurrence, in such a way that man is determined by himself alone. Thus

man and God seem to be rather two causes acting coordinately, like two

men rowing a boat, than two causes of which one is subordinate, acting

under the impulsion of the superior cause.

For Thomists, on

the other hand, operative actual grace does not merely urge by moral

impulsion, but operates physically as well, with respect to the

performance of an act and sometimes even leads to free choice; that is,

when man cannot move himself to this choice deliberately by virtue of a

previous higher act, such as the moment of conversion to God or the acts

of the gifts of the Holy Ghost, which proceed from a special

inspiration. Cooperative actual grace, moreover, is also a physical

impulsion under which man, by virtue of a previous act of willing the

end, moves himself to will the means to the end.

Let us examine:

1. the text of St. Augustine, 2. the interpretation of Molina, 3. the

article of St. Thomas referred to and also the reply to objections (Ia

IIae, q. 9, a. 6 ad 3). The teaching of St. Thomas will be defended.

1. St.

Augustine. The text of St. Augustine (De gratia et libero

arbitrio, chap. 17) reads thus: “God Himself works so that we may

will at the beginning what, once we are willing, He cooperates in

perfecting; therefore does the Apostle say: ‘Being confident of this

very thing, that He who hath begun a good work in you, will perfect it

unto the day of Christ Jesus’ (Phil. 1:6). That we should will

therefore, He accomplishes without us; but when we do will, and so will

as to do, He cooperates with us.”

2. Molina’s

opinion. For Molina, operative grace is nothing more than prevenient

grace morally urging us; cooperative grace assists us. Hence, according

to Molina, “a person assisted by the help of less grace may be

converted, although another with greater help does not become converted

and continues to be obdurate.” Cf. Concordia p.565.

As Father Del

Prado observes (De gratia, I, 226): “Molina departs from the ways

of St. Thomas in the explanation of the nature of divine grace,

operative and cooperative, and refuses to admit that the grace of God

alone transforms the wills of men or that only God opens the heart.

Consequently, whether Molina will have it or not, although it is God who

stands at the gate and knocks, it is man who begins to open and man

alone who, in fact, does open it . . . Hence the beginning of consent,

for Molina, resides in man, who alone determines himself to will,

whereas God, who stands at the gate knocking, awaits his will.” Before

this beginning of consent proceeding from us alone, Molina maintains,

however, against the Semi-Pelagians, that there are moral divine

impulsions drawing us as well as the indeliberate movement of our will,

but that they are equal and even stronger in him who is not converted.

This is corroborated by some of his

well-known propositions; for instance, in the Concordia under the

heading “auxilium” in the index, we read: “It may happen that with equal

assistance, one of those who are called may be converted and another not

converted” (p. 51). Furthermore, “he who is helped by the aid of less

grace may be con-verted, although another with more does not become

converted and perseveres in his obstinacy” (p. 565). Hence, as Lessius

declares, “not that he who accepts does so by his freedom alone (since

there was grace attracting him), but that the turning point arose from

his freedom alone and thus not from a diversity of prevenient helps.”

(Cf. Salmanticenses, De gratia, tr. XIV, disp. 7.)

St. Thomas, on

the contrary, referring to the words of St. Matthew (25:15), “And to one

he gave five talents, and to another two, and to another one,” comments:

“He who makes more effort has more grace, but the fact that he makes

more effort requires a higher cause.” Again, with reference to the

Epistle to the Ephesians (4:7), “to everyone of us is given grace,

according to the measure of the giving of Christ,” he repeats this

observation, and similarly in Ia IIae, q. 112, a. 4, on whether grace is

equal in all men.

The root of the

disagreement is manifold, but the principal point of contention is the

one mentioned by Molina himself in the Concordia (q.14, a. 13,

disp. 26, p. 152). “There are two difficulties, it seems to me, in the

teaching of St. Thomas (Ia, q. 105, a. 5); the first is that I do not

see what can be that impulse and its application to secondary causes, by

which God moves and applies them to act . . . Wherefore I confess

frankly that it is very difficult for me to understand this impulsion

and application which St. Thomas requires in secondary causes.

But, as Father

Del Prado observes (op. cit., p. 227): “In this article,

such application and impulsion is clearly affirmed even in free

secondary causes, and so, with respect to the interior act of the free

will, ‘the will is situated as moved only and not as moving, God alone

being the Mover. Here, as we shall presently see, physical premotion conquers,

rules, and triumphs. Thence proceed the anger and the unmentioned

recriminations which Molina gives vent to against the teaching of St.

Thomas, under the pretense of vindicating St. Augustine.”

For Molina

holds (Concordia, disp. 42, p. 242) that according to St. Augustine (De

gratia et libero arbitrio, chap. 17) “whatever God effects in us

that is supernatural, until the moment when He leads us to the gift of

justification, whether we cooperate in it by our free will or not, is

called ‘operative grace’; that, however, by which He henceforth assists

us to fulfill the whole law and persevere . . . is called ‘cooperative

grace.’. . . And this is plainly the sense and intention of Augustine in

this place when he draws a distinction between operative and cooperative

grace, which will be obvious in the clearest light to anyone examining

that chapter, notwithstanding the fact that St. Thomas understands

Augustine otherwise in the two articles quoted (Ia IIae, q. III, a. 2

and 3), as well as Soto (De natura et gratia, Bk. I, chap. 16)

and some others.”

However, Molina

is obliged to explain on the following page (p. 243) the words of St.

Paul to the Philippians (2:13): “It is God who works in you, both to

will and accomplish,” with regard to which Augustine had said:

“Therefore, that we will is brought about by God, without us; but when

we will, and so will as to act, He cooperates with us.” With regard to

this text, Molina says: “But neither does Augustine mean to assert that

we do not cooperate toward willing, by which we are justified, or that

it is not effected by us, but by God alone. That certainly would be both

contrary to faith and opposed to the teaching of Augustine himself in

many other places.”

Referring to

these last words of Molina, Father Del Prado (op. cit. I,

226) declares: “Does St. Thomas teach something contrary to faith in

drawing the distinction between operative and cooperative grace? . . .

From the lofty and profound teaching of St. Thomas propounded in this

article, wherein all is truth and brilliance, does something follow

which is contrary to the Catholic faith and the teaching of Augustine

himself? . . . Molina departs from the ways of St. Thomas (since he will

not admit that God applies and moves the will beforehand, but). . . . He

holds that, while God, drawing the soul morally, stands at the gate and

knocks, it is man who begins to open, and man alone who actually does

open.” In the Apocalypse (3:20) we read: “I stand at the gate, and

knock. If any man shall hear My voice, and open to Me the door, I will

come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with Me.” But man does not

open it alone; he opens in fact according as God knocks efficaciously.

Otherwise how would the words of St. Paul be verified: “What hast thou

that thou hast not received?” In the business of salvation, not

everything would then be from God.

Conclusion with

respect to Molina’s opinion. For Molina and Suarez and the Molinists in

general, operative grace is nothing else but prevenient grace which

urges morally, but does not really assist,

and only cooperative grace

assists the soul.

Suarez himself admits this.

For the beginning of consent,

according to Molina, comes from man, who alone determines himself to

will; while God almost waits for our consent. Indeed, for Molina, “he

who is aided by the help of less grace may be converted, whereas

another, with greater help, is not converted and persists in his

obduracy” (op. cit., p. 365).

Thus the salient

point at issue, as Father Del Prado says (op. cit., I,

223), is: “Whether the free will of man, when moved by the gratuitous

impulsion of God to accept and receive the gift of the grace of

justification, at that very instant of justification, in in a condition

of being moved only, and not of moving, while God alone moves. When God

stands at the gate of the heart and knocks, that we may open to Him, is

it man who alone opens his heart, or God who begins to open and is the

first to open and, having opened, confers upon us that we, too, may

ourselves open to Him?” This is the question which St. Thomas solves in

that celebrated article 2 and explains more fully below, in question

113. But Molina jumps from what precedes our justification to what

follows it, and is not willing to examine the very moment when the free

will of man is moved by God, through the love of charity, and from one

who is averse to Him is made a convert to Him, and is intrinsically

transformed by God who infuses sacnctifiying grace.” This is the crux of

the present controversy.

3. St. Thomas’

opinion. St. Thomas rightly interprets St. Augustine (cf. Del Prado,

op. cit. I, 224 and 202); for Augustine declares:

“God, cooperating with us, perfects what He began by operating in us;

because in beginning He works in us that we may have the will, and

cooperates to perfect the work with us once we are willing. For this

reason the Apostles say (Phil. 1:6): ‘Being confident of this very

thing, that He, who hath begun a good work in you, will perfect it unto

the day of Christ Jesus.’ That we should will is, therefore,

accomplished without us; but once we are willing, and willing to such an

extent that we act, He cooperates with us; however, without either His

operation or His cooperation once we will, we are incapable of any good

works of piety. With regard to His bringing it about that we will, it is

said in Philippians (2:13): ‘For it is God who worketh in you, . . . to

will.’ But of His cooperation, when we already are willing and willingly

act, it is said: ‘We know that to them that love God, all things work

together unto good’ (Rom. 8:28).” St. Augustine reiterates this opinion

in chapters 5 and 14 of the same book.

Again, writing to

Boniface (Bk. II, chap. 9): “God accomplishes many good things in man

which man does not accomplish (operative grace); but man does nothing

good which God does not enable him to do (cooperative grace).” This is

observed by the Council of Orange (c. 20, Denz., no. 193).

Moreover,

according to Augustine, operative grace is not simply grace urging

equally him who is converted and him who is not, for Augustine repeats

in several places, with reference to predestination: “Why does He draw

this man and not that? Do not judge if you do not wish to err” (Super

Joan., tr. 26; cf. Ia, q. 23, a. 5). This teaching of Augustine is

mentioned by St. Gregory (Moral., Bk. XVI, chap. 10) and by St.

Bernard (De gratia et libero arbitrio, chap. 14); both are quoted

by Del Prado (op. cit., I, 203).

In article 2 of

the present question there are two conclusions, one concerning actual

grace and the other habitual grace.

First

conclusion. Actual grace is

properly divided into operative and cooperative grace.

a)

Council of Orange. Above and beyond the aforesaid authority of

St. Augustine, this conclusion is supported by the Council of Orange (Denz.,

no. 177, can. 4): “It must be acknowledged that God does not wait upon

our wills to cleanse us from sin, but also that we should wish to be

cleansed by the infusion and operation of the Holy Ghost in us.” In

canon 23 it is said that God prepares our wills that they may desire the

good. Again (can. 25, Denz., no. 200): “In every good work, it is not we

who begin . . . but He (God) first inspires us with faith and love of

Him, through no preceding merit on our part.” All these texts pertain to

operative grace, as does the beginning of canon 20 (Denz., no. 193), as

follows: “God does many good works in man which man himself does not

do.” But the second part of this canon applies to cooperative grace,

thus: “But man does no good works which God does not enable him to do.”

b )

Theological proof.

An operation is

not attributed to the thing moved, but to the mover; for example, the

fact that a cart is drawn is attributed to the horse.

But in the first

interior act, the will is situated as moved only, whereas God is the

mover; whereas in the exterior act, ordered by the will, the will is

both moved and moves.

Therefore in the

first act the operation is attributed to God, and therefore the grace is

termed operative; in the second act the operation is attributed not only

to God, but also to the soul, and the grace is termed cooperative.

The major is

clear with regard to an inanimate thing that is moved, as the cart is

moved by the horse, but if the thing moved is a living thing and the

operation is a vital act, it is elicited, indeed, from it. Thus, the

very first act of the will is elicited vitally from it; however, the

will is not said to move itself to it, properly speaking, since, as

explained above (Ia IIae, 9.9, a.3), “the will, by the very fact that it

desires the end, moves itself to will those things which conduce to the

end; just as the intellect, by the fact that it knows a principle,

reduces itself from potency to act, with respect to the knowledge of the

conclusion.” To move oneself is, indeed, to reduce oneself from potency

to act. Hence it is not to be wondered at that, in this act wherein the

will cannot move itself by virtue of a previous effcacious act of the

same order, it should be referred to as moved only, and the operation

attributed to God.

The minor needs

explanation. What is this interior act? It is manifold. It is that first

of all by which we desire happiness in general, and for this,

supernatural help is not required (cf. Ia IIae, q. 9, a. 4, c. 2); it is

particularly, according to St. Thomas (ibid.), “that the will

which previously desired evil now begins to will the good.” This is

explained (IIa, q. 86, a. 6 ad I): “The effect of operative grace is

justification of the wicked, as stated in Ia IIae, q. 113, a. 1-3, which

[justification] consists not only in the infusion of grace and the

remission of sins, but also a movement of the free will toward God,

which is the act of formed faith, and a movement of the free will in

relation to sin, which is the act of penance. But these human acts are

present as effects of operative grace, produced in the same way as the

remission of sins. Hence the remission of sin is not accomplished

without an act of the virtue of penance, even if it is the effect of

operative grace.” These acts are therefore vital, rather are they even

free, but the will does not move itself toward them, strictly speaking,

by virtue of a previous eflicacious act of the same order, since

beforehand, a prior act of this kind did not exist.

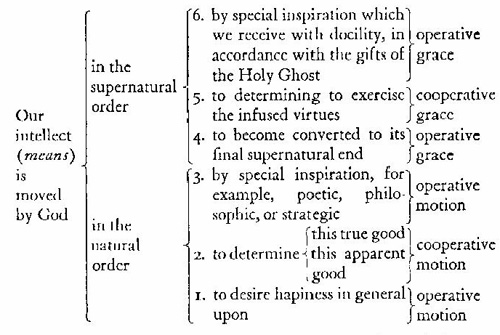

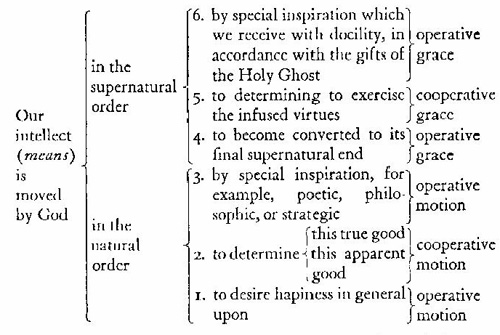

The following

synopsis, which we have already given in the introduction and which can

now be explained, should be read in an ascending order, from the natural

to the supernatural.

We explained this

elsewhere (Christian Perfection and Contemplation, p. 285). From

the same point of view Father Del Prado has made an excellent study of

the present article (op. cit., I, 206, 235; II, 220); and

before him, Cajetan, commenting on this article, as well as Soto, Lemos,

and Billuart.

Wherefore St.

Thomas declares in the reply to the second objection: “Through the

movement of the free will, when we are justified, we consent to the

justice of God.” But man does not move himself, properly speaking, to

justification; he is moved to it, freely of course, but moved

nonetheless; hence it is the effect of operative, not cooperative grace.

This operative

grace given at the instant of justification is, as Father Del Prado

states (ibid., II, 220), a kind of introduction to all the free

movements toward the good, meritorious for salvation, a quasi door into

the supernatural order, and, as it were, the first step in the work of

divine predestination. And this first act of charity is rather a simple

willing of the final end than election, for election as such, properly

so called, belongs to those things that are means to an end. Cf. IIa

IIae, q. 24, a. I ad 3: “Charity, the object of which is the final end,

should rather be said to reside in the will than in free choice.” Hence

operative grace includes not only vocation to the Christian life or the

prompting by which God knocks at the gate (wherein our cooperation is

non-existent; they precede our consent at any time whatever), but also

the movement by which we are justified, freely consenting to it. Thus

we read in Ezechiel (36:25f.): “I will pour upon you clean water, and

you shall be cleansed from all your filthiness . . . . And I will give

you a new heart, and put a new spirit within you: and I will take away

the stony heart out of your flesh, and will give you a heart of flesh.”

Again in the Acts of the Apostles (16:14): “whose heart [Lydia’s] the

Lord opened to attend to those things which were said by Paul.”

Hence, when God

says (Apoc. 3:20): “Behold, I stand at the gate and knock,” it is not

man who begins to open and separates himself from sinners. Rather, as

God opened the heart of Lydia, so does He open the heart of any of the

just at the instant of justification. “God begins to open, He first

opens, and in doing so, confers upon us that we, too, may open to Him,”

as Father Del Prado so well expresses it (op. cit., I,

223).

The third example

of operative grace is the special inspiration we receive with docility

by means of the gifts of the Holy Ghost, according to Cajetan (cf. Ia

IIae, q. 68, a. 1-3), since “the gifts are certain habits by which man

is perfected so as to obey the Holy Ghost promptly. . . . But man, thus

acted upon by the Holy Ghost, also acts, according as it is by free

choice,” as stated in the same article 3, ad 2. Hence these operations

proceeding from the gifts, for instance, from the gift of piety in the

will, are vital, free, and meritorious, and yet the will does not,

properly speaking, move itself to perform them, as it moves itself by

deliberation to works of virtue in a human manner, but is specially

moved by the Holy Ghost. This is well explained by St. Thomas in his

Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (8:14, lect. 3), a beautiful

commentary on the present article. Regarding the words: “Whosoever are

led by the Spirit of God, they are the sons of God,” he writes as

follows: “They are said to be led who are moved by some superior

instinct: thus we say of brutes, not that they act, but that they are

led or impelled to act, since they are moved by natural instinct, and

not by personal movement, to perform their actions. Likewise the

spiritual man is inclined to perform some act, not, as it were, mainly

by the movement of his own will, but by an instinct of the Holy Ghost.”

This does not, however, prevent spiritual men from using their will and

free choice, since what the Holy Ghost causes in them is precisely the

movement of their will and free choice, according to Phil. 2:13: “For it

is God who worketh in you, both to will and to accomplish.”

In the

explanation of the minor, we now come to the question of cooperative

grace. This is conferred for good works in which our will is not only

moved, but moves itself, that is, when, already actually willing the

final supernatural end, it converts itself to willing the means

conducive to that end. This act is said to be external, although it may

be only internal, since it is commanded by the will in virtue of a

previous efficacious act of the same order. Thus it is in the use of the

infused virtues, by deliberation properly so called, that the act is

performed in the human mode, for example, when the will commands an act

of justice or religion or fortitude or temperance, by virtue of a

previous act of love of God. Not only are these acts vital, free, and

meritorious, but the will properly moves toward them or “determines

itself to will this or that,” as is said in the well-known reply to the

third objection, Ia IIae, q. 9, a. 6.

It is this

cooperative grace that is referred to in Sacred Scripture; indeed there

is even a comparison made with operative grace; for example, in Ezech.

36:27: “And I will put My spirit in the midst of you [operative grace]:

and I will cause you to walk in My commandments, and to keep My

judgments, and do them [cooperative grace].” Again in I Cor. 15:10: “But

by the grace of God, I am what I am [operative grace]; and His grace in

me hath not been void, but I have labored more abundantly than all they:

yet not I, but the grace of God with me.” This latter is cooperative

grace.

The Angelic

Doctor always speaks in harmony with these texts. According to him,

under operative grace, the will elicits its act vitally, in fact, it

freely consents to the divine motion or inspiration, but it does not

strictly move itself by its own proper activity in virtue of a previous

efficacious act of the same order, for this previous efficacious act is

wanting at that time; for example, in justification, in the acts of the

gifts of the Holy Ghost, such as the gift of piety. With respect to

justification, St. Thomas declares (Ia IIae, q. III, a. 2 ad 2): “God

does not justify us without ourselves, since by the movement of free

will when we are justified we consent to the justice of God. However,

this movement is not the cause of grace, but its effect; hence the whole

action pertains to grace.” Again, he states (IIIa, q. 86, a. 4 ad 2): It

pertains to grace to operate in man, justifying him from sin, and to

cooperate with man in right action. Therefore the remission of sins and

of the guilt deserving of eternal punishment belongs to operative grace,

but the remission of guilt which merits temporal punishment pertains to

cooperative grace, that is, according as man, enduring sufferings

patiently with the help of divine grace, is also absolved from the guilt

of temporal punishment, . . . the first effect is from grace alone, the

second from grace and free will.” (See also q. 86, a. 6 ad I.) It is

previously declared (9.85, a. 5 c.): “Penance as a habit is immediately

infused by God, without any principal operation on our part, but not

however without our disposing ourselves to cooperate by some acts.”

Conclusion

of Father Del Prado (op. cit., I, 21 I ): By operative

grace God operates in us without our acting or moving ourselves, but not

without our consent. Cf. a. 2: Thus in the instant of justification and

in the operation of the seven gifts. In fact, certain operative grace is

even antecedent in time to our consent, such, for instance, as vocation

and admonition when God stands at the gate and knocks before it is

opened. Here, however, the free consent may, broadly speaking, be called

cooperation on our part; but not in the strict and formal sense in which

the term is used by St. Thomas in this article. On the contrary, by

cooperative grace, God works in us, not only with our consent, but with

our action or motion. This is the Thomistic interpretation of St.

Augustine’s teaching; it is eminently profound and in full conformity

with faith.

Corollary.

Thus the opposition between St. Thomas’ doctrine and that of heresy is

manifest. Of the operative actual grace by which we are justified (cf.

Del Prado, op. cit., I, 213): Calvin holds that free will

is moved without any action on its own part, and is merely passive.

Jansen holds that free will is moved necessarily, and cannot resist even

if it wills to do so; Pelagius holds that free will begins to move

itself to this first volition; Molina holds 1. that free will is moved

by virtuous, indeliberate impulses which, willy-nilly, are supernatural.

2. Then it begins to deliberate within itself, freely accepting them. In

his first contention, Molina borders on Jansenism; in the second he does

not seem sufficiently removed from Pelagius. In both respects, the

opinion of Molina deviates from the teaching of St. Thomas. As declared

in the reply to the third objection, grace is not called “cooperative”

in the sense that God here places Himself in the position of a secondary

agent; He ever remains the principal agent. But the will also moves

itself in this case “once the end is taken for granted” in the intended

act, and God assists it in the pursuit of this intended end.

The second

conclusion is that habitual

grace can also be referred to as operative and cooperative (cf. end of

article) since it has two effects:1. it justifies the soul; this is

operative grace, not effectively but formally, that is, it makes

pleasing, just as whiteness makes a thing white, as stated in the reply

to the first objection; 2. it is the root principle of meritorious

works, which proceed from the free will; in this sense it is

cooperative.

First doubt,

arising from the reply to the fourth objection (cf. Del Prado, op.

cit., I, 228): Whether operative and cooperative grace may be the

same grace.

Reply.

Yes, if it is a question of habitual grace, which is at the same time

justifying (formally) and the root principle of meritorious works. This

is clearly stated here in the answer to the fourth objection and in

article 3 ad 2, where it is clearly a question of habitual grace, which

is said to remain numerically the same in glory, where it is

consummated. Cf. also De veritate, q. 27, a. 5 ad I, and IIIa, q.

60, a. 2; q. 72, a. 7. Sacramental grace is a mode of habitual grace and

is applied with various effects.

But if the

question is about actual grace, then operative grace and cooperative

grace are not one and the same numerically; for the reason is the same

for actual grace and for the act of the will, of which it is the

principle and beginning. But the act is twofold, interior wherein the

will does not move itself, exterior wherein it does. Therefore there are

likewise two actual graces, for actual grace passes and ceases with the

very operation toward which it moves. John of St. Thomas and the

Salmanticenses hold this opinion.

In fact

sometimes, after an act proceeding from operative grace, there is not

elicited an act for which cooperative grace is required, as is evident

in the case of one who, immediately after absolution and justification,

sins, by not performing the act of virtue which he ought to perform. In

such a one, operative grace efficaciously produced justification freely

accepted, but it did not produce the following act. To produce it a new

actual grace is required, that is, cooperative grace, for there is a new

passage from potency to act, and whatever is moved to a new supernatural

act, is moved supernaturally by another.

Operative actual

grace and cooperative actual grace are therefore distinct, since at

times the first is given without the second or vice versa. But if the

superior and inferior acts are simultaneous, as in infused contemplation

which is prolonged by some discourse, or an inspiration of the gift of

council which is simultaneous with an act of prudence, then perhaps it

suffices that operative grace should be given, provided that, according

to God’s decree, it contains cooperative grace eminently; it is then

more perfect than if it did not contain it. Second doubt. Whether

operative actual grace requires a twofold motion, namely, moral on the

part of the object and physical on the part of the subject. (Cf. Del

Prado, op. cit., I, 233.)

Reply.

I reply in the affirmative, together with John of St. Thomas and Father

Del Prado; for operative grace first enlightens the intellect, then

touches the will and causes a sudden desire for the object proposed

through the representation of the intellect; and this is the in-spiration

that opens the heart, as the heart of Lydia was “opened to attend to

those things which were said by Paul” (Acts 16:14). Hence operative

grace not only excites by moral movement, but also operates physically,

so that by it the heart of man is opened and led not only to

indeliberate acts but sometimes to consent as well, for example, in

justification or in acts of the gifts of the Holy Ghost.

Third doubt.

What are the effects of operative grace in us? There are three. (Cf.

Father Del Prado, op. cit., I, 234.)

1. The

enlightenment of the intellect and the objective pulsation of the heart:

this is a moral movement prior to any consent; thereupon the acts are

indeliberate, and with respect to this stage operative grace is nothing

but a grace which urges.

2. The

application of the free will to the holy affection or action, that it

may be converted to God; this application is the complement in the

secondary cause of the power to operate.

3. The

very act of willing, applied to the action, namely, the very act of

believing, hoping, and loving: in these acts the will does not remain

passive, but elicits the acts freely. However, the will does not

properly move itself to such an act as a result of a preceding act,

since this act is first in the order of grace and relates to the final

end. Hence, contrary to the opinion of Molina, operative grace

determinately moving toward these acts is more than a mere urging, and

yet liberty is safeguarded, according to St. Thomas.

Fourth doubt. Whether cooperative grace produces in us three

similar effects. Undoubtedly, for cooperative grace is also a previous

movement according to a priority not of time but of causality. But these

three effects are in another way, since with cooperative grace the will

moves itself on account of some preceding act; thus it wills,

presupposing the end already intended. On the contrary, with operative

grace the will wills by tending toward the end, and the act of the will

resembles that first act of the angels discussed in Ia, q. 63, a. 5, or

that first act of the soul of Christ which is considered in IIIa, q. 34,

a. 3. In the first instant of His conception, Christ merited not

incarnation but the glory of immortality, just as an adult at the

instant of justification acquires not the grace of justification but the

subsequent grace.

Final corollary. We may now read again the well-known reply to

the third objection of Ia IIae, q. 9, a. 6, and easily grasp its

meaning: “Occasionally God moves some men especially toward willing

something determinate which is good, as in those whom He moves by grace,

as stated below,” that is, in our article 2. This is operative grace

moving determinately, but with which liberty still remains.

SOME FALSE NOTIONS CONCERNING OPERATIVE AND COOPERATIVE GRACE ( CF.

SALMANTICENSES)

Operative grace

does not consist in an indeliberate act, according as it depends upon

God, as Ripalda would have it, since an indeliberate supernatural act

presupposes operative help moving one to this act. Nor does it consist

in an indeliberate act, with God’s assistance, as Suarez holds, for God

is not united to us in the manner of an operative power.

Again, in

opposition to Alvarez and Gonet, operative grace is not a simple

movement applying a previous one, for operative grace thus understood

pertains to all operations of the will, indeliberate as well as

deliberate, as these authors admit, whereas St. Thomas declares that

operative grace, specifically so called, pertains only to the act of the

will by which it is moved toward something freely, but does not move

itself by discursive deliberation.

Cooperative grace

is not the indeliberate act itself inclining toward deliberate consent,

because cooperative grace, and not this indeliberate act, has an

infallible connection with the deliberate operation to which it moves us

and which, in fact, it produces, since by such grace God cooperates and

influences the eliciting of the aforesaid act. But the indeliberate

affection, left to itself, has no infallible connection with deliberate

assent, since we often resist a sudden inspiration or inclination;

therefore cooperative grace cannot consist in an indeliberate affection;

but there must be added a motion which joins the indeliberate act with

the deliberate act or which ensures that the deliberate act is

effective. Cf. below, p. 230, the opinion of Gonzales, where it is a

matter of the fundamental distinction between efficacious and sufficient

grace.

ARTICLE III.

WHETHER GRACE IS

PROPERLY DIVIDED

INTO PREVENIENT

AND SUBSEQUENT GRACE

State

of the question. This article

is intended to explain the classical division of grace, according to

Augustine, De natura et gratia, chap. 31, and ad Bonifacium,

Bk. 11, chap. 9, as here cited at the end of the article. These terms

should be carefully defined that it may be clear wherein lay the error

of the Pelagians and Semi-Pelagians, who de-nied the necessity of

prevenient grace. According to them, generally, every internal grace was

subsequent with respect to free will; only external preaching of the

word was antecedent, according as the beginning of salvation came from

us and not from God. Thus did they interpret the words of Apoc. 3:20: “I

stand at the gate, and knock. If any man shall hear My voice, and open

to Me the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he

with Me.”

We shall

presently see that grace can never be thus termed “subsequent” with

respect to free will, but only in the sense that it follows another

grace or another effect of grace; cf. below, Ia IIae, q. 112, a. 2:

“Whatever preparation (for grace) may be present in man is derived from

the help of God moving the soul to good”; and in IV Sent., d. 17,

q. I, a. I, solut. 2 ad 2: “Our will is entirely attendant upon divine

grace and in no way before hand.”

Conclusion.

Grace, habitual as well as actual, is properly divided into prevenient

and subsequent.

Scriptural

proof, in the argument Sed

contra; namely, that the grace of God proceeds from His mercy. But

it is said (Ps. 58:11): “His mercy shall prevent me,” and again (Ps.

22:6): “Thy mercy will follow me.” Therefore.

Likewise in the

prayers of the Church; the collect Pretiosa: “Anticipate, O Lord, we

beseech thee, our actions by Thy inspiration, and continue them by Thine

assistance; that every one of our works may begin always from Thee, and

through Thee be ended.” The collect for the Sixteenth Sunday after

Pentecost: “O Lord, we pray Thee that Thy grace may always go before and

follow us.” And the collect of Easter Sunday: “Grant that the vows Thou

inspirest us to perform, Thou wouldst thyself help us to fulfill.”

Similarly on the

authority of St. Augustine, here cited in the body of the article, from

De natura et gratia, chap. 31: “(God) precedes us that we may be

healed; He follows us that, even healed, we may yet be invigorated. He

precedes us that we may be called; He follows us that we may be

glorified. He precedes us that we may live piously;

He follows us

that we may live with Him forever, since without Him we can do nothing.”

Theological

proof.

Grace is properly

classified according to its various effects.

But there are

five effects appointed to grace: 1. that the soul may be healed; 2. that

it may will the good; 3. that it may eficaciously perform the good it

wills; 4. that it may persevere in the good; 5. that it may attain to

glory.

Therefore the

grace causing the first effect is properly termed “prevenient” with

respect to the second effect, and as causing the second it is called

“subsequent” in relation to the first effect; and so with the rest. Thus

the same act is at once prevenient and subsequent with respect to

different effects.

Corollary.

Thus grace is called prevenient with respect to some following act,

although it is also prevenient with respect to the act toward which it

moves immediately, according as it is previous to it with the priority

of causality. And grace is not said to be subsequent in relation to free

will, as Pelagius held, but relative to another grace or effect of

grace.

As St. Thomas

remarks (De veritate, q. 27, a. 5 ad 6): “Prevenient and

subsequent grace may be understood in another way with respect to the

man whom it moves; thus prevenient grace causes a man to will what is

good, and subsequent grace causes him to perform the good which he has

willed.” As Augustine declares in the Enchiridion, chap. 32: “He

precedes the unwilling, that he may will, and follows the willing lest

he will in vain.”

Reply to first

objection. Since the

uncreated love of God for us is eternal, it is always prevenient. (Cf.

Del Prado, op. cit., I, 247.)

Corollary 2.

Both operative and cooperative grace, since they move toward diverse

acts, may be called prevenient and subsequent.

Doubt.

Whether prevenient and subsequent grace may be the same grace

numerically. The solution is found in the reply to the second objection,

that is, in the case of habitual grace, yes; but in that of actual

grace, no, for the same reason as for operative and cooperative grace.

For it is evident that the same habitual grace, numerically, is called

prevenient inasmuch as, justifying us, it precedes meritorious works; it

is called subsequent inasmuch as it will be consummated, thus it is

called glory.”

In fact, St.

Thomas expressly states here in the reply to the second objection:

“Subsequent grace pertaining to glory is not different numerically from

prevenient grace by which we are justified now; for as the charity of

the wayfarer is not made void but perfected in heaven, so also can this

be said of the light of grace, for neither of them bears any

imperfection in its principle.”

But if it is a

question of actual grace, which ceases with the very act toward which it

moves immediately and of which it is the beginning, then it is

multiplied along with the acts enumerated above, as we said before of

operative actual grace and cooperative actual grace.

To complete this

Question III on the division of grace, two articles must be added since

the Council of Trent and the condemnation of Jansenism: 1. The

distinction between exciting or stimulating grace and assisting grace,

which was considered by the Council, Sess. VI, chap. 5; 2. The

difference between sufficient and efficacious grace, in respect to which

the Protestants and Jansenists erred.

THE DIVISION OF ACTUAL

GRACE INTO STIMULATING AND ASSISTING GRACE (CF. DEL PRADO, OP.

CIT., I, 243)

This division is

explained at the Council of Trent, Sess. VI, chap. 5 (Denz., no. 797):

“It is declared, moreover, that the beginning of this very justification

in adults is received from God through Christ Jesus by prevenient grace

(can. 3), that is, by His vocation, in that none are called on account

of their own existing merits; that they who were turned away from God by

sin, may be disposed by His stimulating and assisting grace to become

converted to their own justification, freely (can. 4 and 5) assenting to

and cooperating with the same grace.”

According to this

text, grace rousing one from the sleep of sin by moral movement, that

is, by enlightenment and attraction, and grace assisting one to will the

good, by the application of the will to its exercise, are included under

prevenient grace, which precedes the free consent of man’s will, whereby

we consent to justification and may be prepared for it. Hence this

prevenient grace to which the Council refers is the same as the

operative grace considered by St. Thomas in article two, especially in

the reply to the second objection: “God does not justify us without

ourselves, since by the movement of free will, when we are justified, we

consent to the justice of God. However, this movement is not the cause

of grace [as the Semi-Pelagians held], but its effect; hence the whole

operation belongs to grace.” (Cf. Del Prado, De gratia, I, 228.)

Thus is

corroborated our interpretation of article two, that is: operative grace

is not only stimulating but assisting. Under Sess. VI, chap. 5 of the

Council the same doctrine is explained as in article two of the present

question (III). The Council of Trent, Sess. VI, can. 4 (Denz., no. 814)

uses the term “moving grace” for assisting grace. Doubt. Whether the

prevenient grace which stimulates the intellect and assists in the

application of the will is absolutely prior to our consent, or

subsequent to it. How are we to understand the following text of the

Apocalypse (3:20)? “Behold, I stand at the gate and knock. If any man

shall hear My voice, and open to Me the door, I will come in to him.”

Reply.

This grace is, with respect to its efficient cause, absolutely prior to

our consent, according to St. Thomas (Ia IIae, q. III, a. 2 ad 2; q.

113, a. 8 c.). At the same instant: 1. there is an infusion of grace; 2.

a movement of the free will with respect to God; 3. a movement of the

free will in regard to sin; 4. the remission of sin. Similarly in the

answers to the first and second objections. (Cf. Dominic Soto, De

natura et gratia, Bk. I, chap. 16, and Del Prado, De gratia,

I, 245.)

Corollary.

Del Prado, op. cit. (I, 248): From the notion of operative

and cooperative grace, propounded by St. Thomas in article two, it can

easily be demonstrated that the gratuitous movement of God, whereby He

impels us to meritorious good, is efficacious, not on account of the

consent of the free will that has been moved, but on account of the will

and intention of God who moves it, as St. Thomas expressly declares in

the following question (112, a. 3).

Even in article

two of the present question, the Angelic Doctor has already said with

reference to operative grace, that “with it, our mens is moved and not

the mover”; and, in the answer to the second objection, that the

movement of the free will, when we are justified and consent to the

justice of God, “is not the cause of grace, but its effect, so that the

whole operation belongs to grace.”

Again in the body

of this second article it is declared of cooperative grace: “And since

God also helps us in this (deliberate) act, both by interiorly

strengthening the will that it may accomplish the act, and by exteriorly

supplying the faculty to perform it, with respect to this kind of act it

is called cooperative grace.”

As a

matter of fact, Molina would not have denied the interpretation of

Augustine given by St. Thomas, were it not declared in this

interpretation that grace is efficacious of itself.

We have treated

this question at length elsewhere: Christian Perfection and

Contemplation; The Three Ages of the Interior Life.

De auxiliis

divinae gratiae, Bk. III, chap. 5, no. 4; cf. Del Prado,

De gratia et libero arbitrio, I, 228.

Operative and

cooperative grace, according to St. Thomas; cf. Ia IIae, q. III,

a.2, o., 4; a.3, c; II Sent., dist. 26, a. 5, o., 4;

De veritate, q. 27, a. 5, I, 2; II Cor., 6, lect. I (at the

beginning); IIIa, q. 86, a. 4, 2; a. 6 ad I; q. 88, a. I, 4.

St. Thomas had

also said, Ia IIae, q.55, a.4 ad 6: “Infused virtue is caused in

us by God, without our action, not however without our consent”;

and further, Ia IIae, q.113, a.3: “By infusing grace God at once

moves the free will to accept the gift of grace, in those who

are capable of this movement.” As Del Prado rightly observes,

op. cit., I, 213: The will cannot strictly move

itself to this first act of charity, for as a supernatural

conclusion is not contained in a natural principle, neither is a

supernatural choice contained in man’s primary natural

intention. In fact, before the gift of justifying grace, the

will of man is turned away from God on account of mortal sin.

Hence it is God who must begin to move the free will of man

determinately by grace toward the initial volition of

supernatural good, as stated in the famous reply to the third

objection, Ia IIae, 9.9, a.6. Similarly, Soto, De nat. et

gratia, chap. 16. This is the true interpretation of St.

Thomas given by Cajetan, Soto, Lemos, etc.; also by the

Salmanticenses, disp. V, dub. VII, no. 165.

|