|

GRACE

Commentary on the Summa theologica

of

St. Thomas, Ia IIae, q. 109-14

By

REV. REGINALD

GARRIGOU-LAGRANGE, O.P.

Translated by

THE DOMINICAN NUNS

Corpus Christi Monastery

Menlo Park, California

B. HERDER BOOK CO .

15 & 17 SOUTH BROADWAY, ST. LOUIS, MO.

AND

33 QUEEN SQUARE, LONDON, W. C.

1952

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Printed in U.S.A.

NIHIL OBSTAT

lnnocentius Swoboda, O.F.M.

Censor Librorum

IMPRIMATUR

X Joseph

E. Ritter

Archiepiscopus

St. Ludovici, die 25a mensis,

julii, 1952

Copyright 1952

B. HERDER BOOK CO.

Vail-Ballou Press, Inc.,

Binghamton and New York

To the holy Mother of God,

Mother of divine Grace,

WHO SWEETLY AND SUBLIMELY TEACHES TO LITTLE

ONES THE MYSTERIES OF SALVATION,

THE AUTHOR DEDICATES THIS WORK

IN TOKEN OF GRATITUDE AND FILIAL OBEDIENCE

PREFACE

We have already explained at length

in the treatise on the one God the doctrine of St. Thomas about the

knowledge and will of God, providence and predestination, and likewise

in the treatise on God the Creator his doctrine on evil. Now it remains

to apply the principles already expounded to the questions of grace, so

that these may be considered in relation to man, and also in relation to

God, the author of grace, who is the subject of sacred theology. Indeed

this science considers all things in relation to God, as optics does in

relation to color and light, mathematics in relation to quantity,

metaphysics in relation to being as such.

Hence the present

treatise On grace depends on the treatise about the divine will

in which we have already set forth the will for universal salvation and

the distinction between antecedent will and consequent will, which is

the ultimate basis, as we shall see, of the distinction between

sufficient grace and efficacious grace.

We presuppose,

likewise, St. Thomas’ doctrine on the intrinsic and infallible efficacy

of the divine decrees, presented in Ia, q. 19, a. 8, which we have

explained at length in the treatise on the one God, refuting the

objections based on the violation of freedom, on insufficiency of help,

and on affinity with Calvinism.

Our treatise on

grace is especially connected with question 20, Part I, on the love of

God: 1. whether love exists in God; 2. whether God loves all things; 3.

whether God loves all things equally; 4. whether God always loves better

things more. In explanation of this last article, we show the value of

the principle of predilection: “Nothing would be better than anything

else (as an act, easy or difficult, natural or supernatural, initial or

final) unless it were more loved and sustained by God.” “What hast thou

that thou hast not received?” (I Cor. 4:7.) As we shall see, this

principle throws a light from on high upon all questions of

predestination and grace. It is likewise the basis of Christian humility

and of our gratitude to God, “who hath first loved us.”

At the same time,

no less emphasis must be placed on another principle of St. Augustine,

formulated and cited at the Council of Trent (Denz., no. 804): “God does

not command the impossible, but by commanding He incites thee to do what

thou canst and to ask what thou canst not, and He assists thee so that

thou mayst be able.” These two principles taken together prevent

opposing deviations; preserve balance of thought and the harmony of the

divine word in regard to these most difficult questions.

AUTHORS TO BE CONSULTED

1.

The teaching of the Fathers on grace

Schwane,

Histoire des Dogmes, tr. Degert, 1904.

J. Tixeront,

Histoire des Dogmes. Vol. I : Théologie anérnicéenne,

1905; Vol.

11: S. Athanase à S. Augustin, 1909; Vol. III: La fin de l’âge

patristique, 1912, p. 274 ff.

Héfele, Histoire des conciles, tr. Leclerq

(Paris, 1908), II, 168.

St. Augustine, De natura et gratia; De gratia

Christi; Enchiridion; Sex libr. aduersus Julianum; De gratia et libero

arbitrio; De correptione

et gratia; De praedestinatione sanctorum; De dono perseuerantiae.

St. Prosper, PL, LI, 155-276.

St. Fulgentius, De gratia et libero arbitrio.

St. Bernard, De gratia et libero arbitrio.

Peter Lombard, Sent., Bk. II, d. 26-28: De

gratia.

St.

Bonaventure and St. Albert the Great, In II Sent.

2. Works of St. Thomas and of Thomists

on grace

St. Thomas, In

II Sent., d. 26-28; la llae, q. 109-14; Contra Gentes, Quaest.

disput.

Principal commentators: Capreolus,

In II Sent.,

d. 26; Cajetan, In Iam

IIae,

q. 109 ff.; Medina, John of St.

Thomas.

Sylvius, Gonet, the Salmanticenses,

Gotti, Billuart.

Soto, De natura et gratia, 1551.

Thomas

Lemos, Panoplia gratiae, 4 vols., 1676.

Alvarez, De auxiliis diuinae gratiae, 1610.

Gonzalez de Albeda, In Iam, q. 19, 1637.

Goudin, De gratia, 1874.

Reginaldus, O.P.,

De mente Conc. Trident. circa gratiam seipsa efficacem, 1706.

Among

recent works by Thomists: Dummermuth: S. Thomas et

doctrina praemotionis physicae,

Paris, 1886; Defensio doctrinae S. Thomas,

1895. N. Del Prado, O.P.,: De gratia et libero arbitrio,

3 vols., Fribourg (Switzerland), 1907. Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P.

“Prédestination,”

“Prémotion.” Schaezler: Natur

und Gnade, Mainz, 1867.

3. Outside the Thomistic School

Molina, Concordia, Paris, 1876.

Suarez, De gratia.

St. Robert Bellarmine, De controversiis

(Prague, 1721), Vol. IV.

St. Alphonsus de

Liguori, De modo quo gratia

operatur; De magno

orationis

medio.

Scheeben,

Natur und Gnade, Mainz, 1861. Strongly

inclines toward

Thomism.

Billot, S.J., De gratia Christi, 2nd

ed., 1921.

Van der Meersch, De divina gratia (Bruges,

1910) and Dict. théol. cath., art., “Grâce.”

J. Ude,

Doctrina Capreoli de influxu Dei in actus uoluntatis humanae, Graz,

1905. This

author favors Thomism.

TREATISE ON GRACE

Ia IIae, q. 109-114

In the first

place something must be said about the position of this treatise in the

Summa theologica. St. Thomas treats of grace in the moral part of

his Summa, for, after the questions of human acts themselves, must be

considered the principles of human acts; first, the intrinsic

principles, namely, good and bad habits, or virtues and vices; secondly,

the external principles of human acts, namely, God’s teaching us by

means of His law, and His assistance to us by His grace.

Hence the

treatise on grace belongs to the moral part of theology no less than the

treatise on law. Moral theology is not a science distinct from dogmatic

theology, since the formal object (objectum formale quod et quo)

is ever the same: God under the aspect of His Deity so far as it falls

under virtual revelation. It would be surprising if the moral part of

sacred theology did not treat of the necessity of grace for doing good

conducive to salvation and of the effects of grace, i.e., justification

and merit. Indeed, if moral theology is deprived of these treatises, it

will be reduced almost to casuistry, which is only its lowest

application, as asceticism and mysticism are its highest applications.

Among Thomistic

commentators the following, along with Cajetan, are especially to be

read: Soto (De natura et gratia), John of St. Thomas, the

Salmanticenses, Gonet, Gotti, Billuart. Cf. also among modern

theologians, Scheeben (Natur und Gnade).

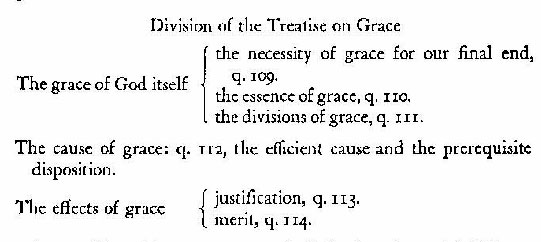

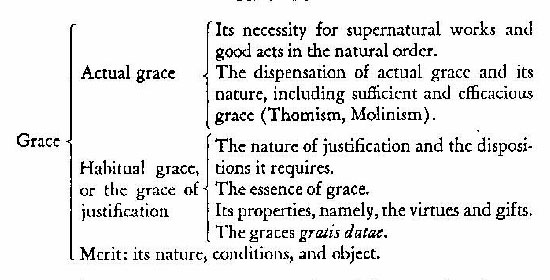

This division of

the whole treatise is methodical, corresponding to the division into

four causes. 1. Grace is considered beginning with the definition of the

word and with reference to its necessity for the end of eternal life and

to its existence. 2. Thus, in regard to its end, grace, as it is the

seed of glory, is defined as a participation in the divine nature and is

determined by the subject in which it resides, that is, the essence of

the soul. 3. After the definition of grace, its subdivisions are given.

Then its efficient cause and its effects are discussed. Thus all those

things which belong to it per se are taken into consideration.

A brief

comparison may be made between this division of St. Thomas and the

division made by various modern writers. Many modern scholars, such as

Tanquerey, divide this treatise into three parts, but this division is

rather material than formal.

This division is

less correct; in treating of the necessity of grace the necessity of

habitual grace is also treated. And in the order of knowledge it is

better to deal with justification, which is an effect of grace, after

considering the essence of grace. Hence Father Billot, S.J., after his

preliminary remarks, rightly divides his treatise on grace according to

St. Thomas. Father Hugon, O.P., does the same, as do many others. Nor

may it be said that St. Thomas did not distinguish clearly between

habitual and actual grace; this distinction is made time and time again

in the articles, and thereby is made evident how St. Thomas perfected

the Augustinian doctrine, regarding grace not only from the

psychological and moral aspects, but ontologically: 1. as an abiding

form, and 2. as a transitory movement.

This entire

treatise is a commentary on the words of our Lord in John 4:10: “If thou

didst know the gift of God,” and our Lord’s discourse by which they are

elucidated, according to St. John. At the same time it may be said that

St. Paul was the apostle of grace who opened to us the deep things of

God, predestination and grace. And the two great doctors of grace are

Augustine, who defended divine grace against Pelagius, and St. Thomas,

of whom the liturgy sings:

“Praise

to the King of glory, Christ,

Who by Thomas, light of the Church,

Filled the earth with the doctrine of grace.”

This

work is a translation of De gratia by Father Garrigou-Lagrange,

O.P.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

PAGE

I. Introduction . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . 3

II. The Necessity

of Grace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .. . 41

III. The Grace of

God with Respect to Its Essence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . 110

IV. The Divisions of Grace . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . 150

V. The Doctrine of the Church . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

182

VI. Sufficient Grace . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .202

VII. Efficacious Grace . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .239

VIII. Excursus on Efficacious Grace . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .265

IX. The Cause of Grace . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .305

X. The Effects of Grace . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .325

XI. Merit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

363

XII. Recapitulation and Supplement . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 399

Appendix .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 504

Index . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . 507

Pages numbers are

those of the book. These files are not divided into pages.

Cf. Ia IIae, q. 90, introd. With regard to this heading, it

should be noted that God assisting by His grace is an extrinsic

principle. Grace, however, is not a principle extrinsic to man,

but inhering in him, as will be explained later.

|